This

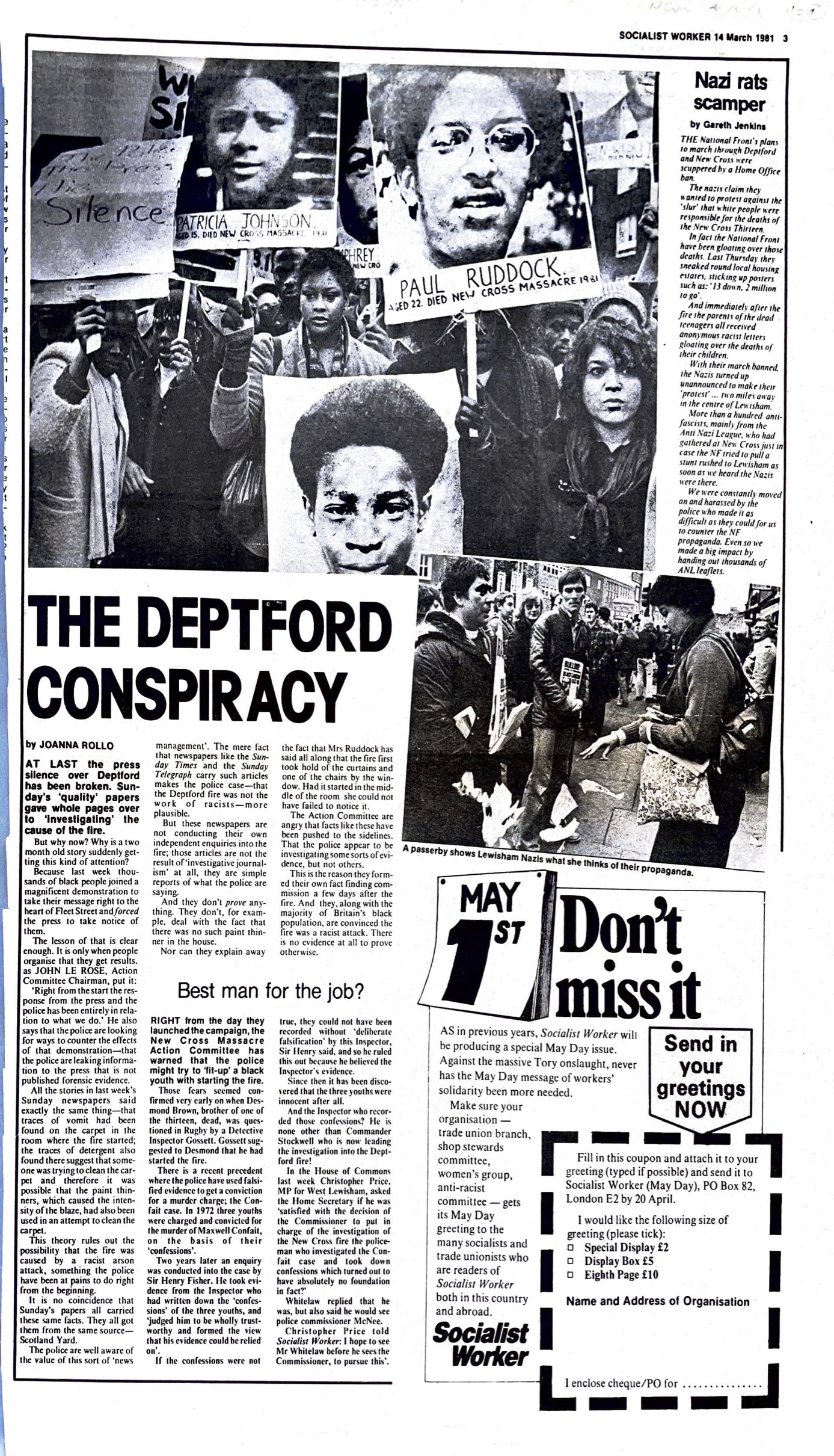

timeline contextualises the New Cross Massacre as a means of

countering both the media and the state’s depoliticisation of the fire.

The

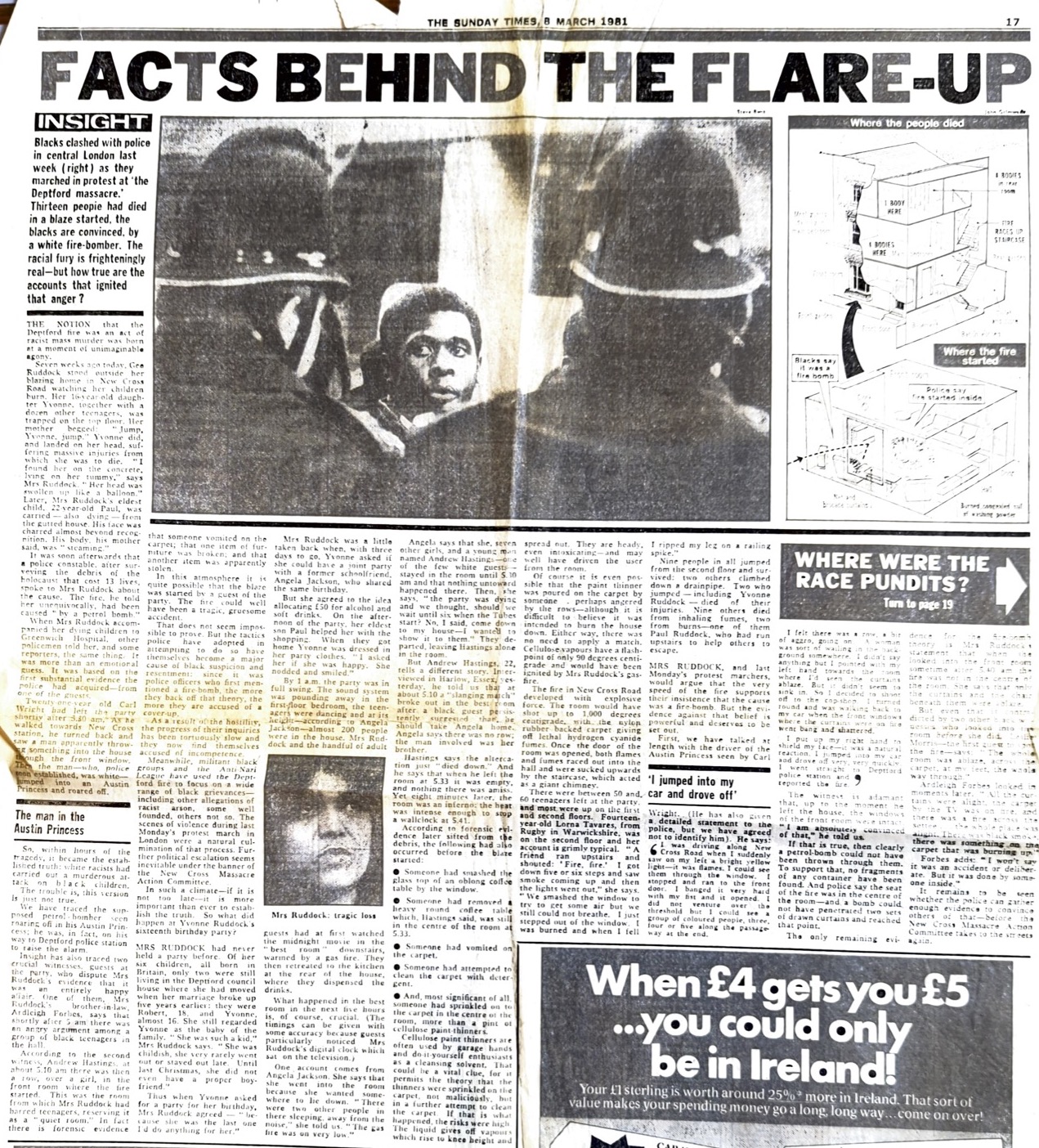

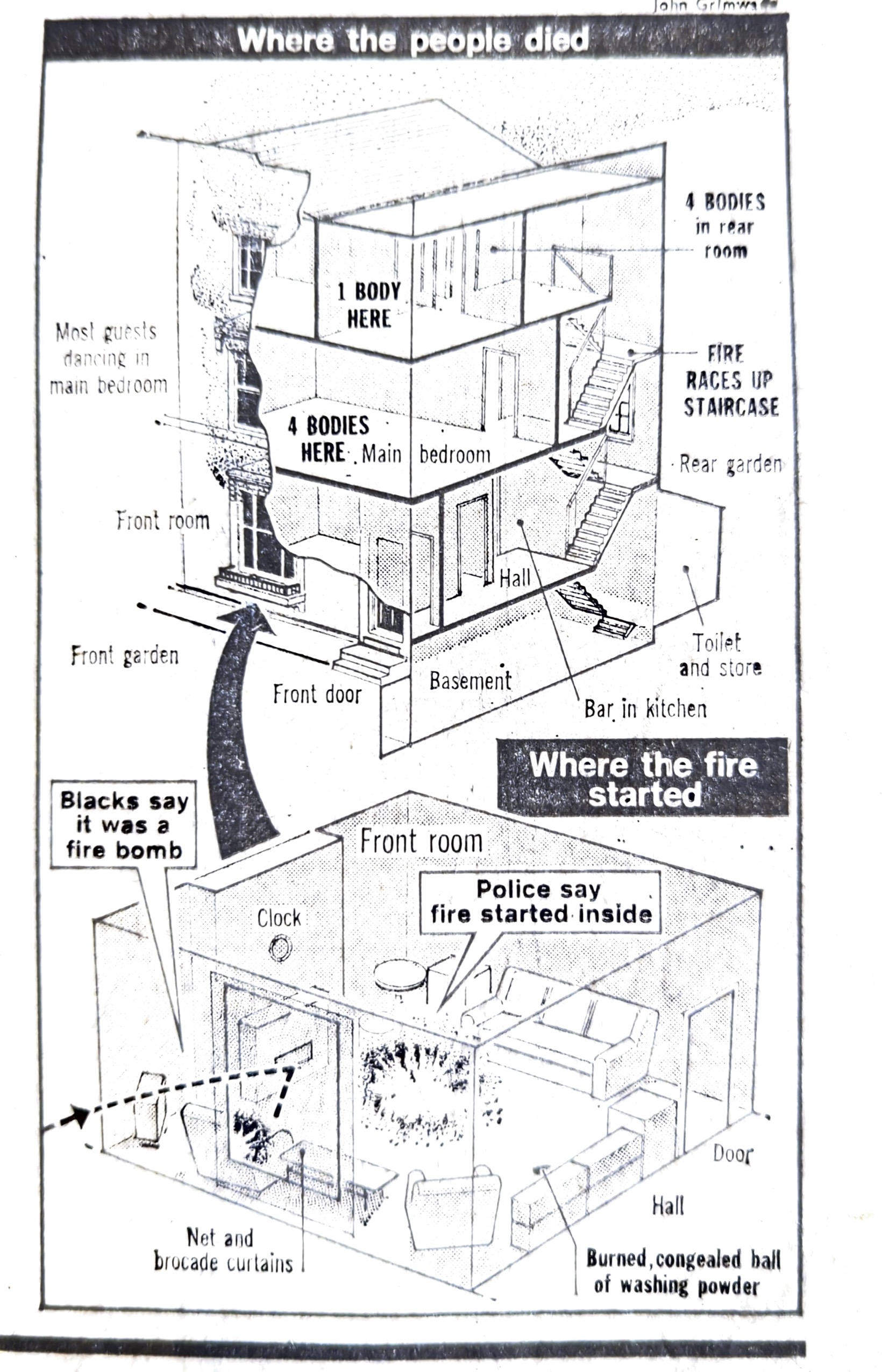

lack of coverage of the Massacre by the media, as well as the

absence of acknowledgement by the state resulted in the

evasion of any national public discourse on the evaluation of Britain’s racist violence and the legislation and state policies that cultivated the environment which made the Massacre possible. The silence of the state in acknowledging the tragedy of the fire was amplified when, one month later, the Stardust nightclub in Dublin burnt down, receiving condolences from both the Queen and then PM Margaret Thatcher.

1 This depoliticisation is a calculative and intentional practice, a form of ‘organised state abandonment’, that has been employed to ensure the continuation of the pattern of racial violence.

2

We can see the

pattern of depoliticising racialised events, particularly with the

uprisings of July 1981 across the country, in Brixton, Birmingham, Coventry, Liverpool, Southall, Manchester, Woolwich, Nottingham, Leicester, Derby, Bradford, among others.

Our timeline zooms in on the month of July to emphasise the intensity of resistance action that happened nationally, inspired by a pattern of police brutality, far-right violence, sus laws, and racist British sentiment fostered by government and media rhetoric.

3

The depoliticisation of these events was institutionalised through the

Hytner Report and the

Scarman Report, both published in 1981, which were government inquiries analysing the causation of the uprisings.

4 The Hytner report concluded that the

Moss Side uprising was a “spontaneous eruption(s) of hate”, placing the event in an ahistorical vacuum by refusing to acknowledge the racial violence which grounded the uprising. The Scarman Report followed suit, which came to the same conclusion regarding the

Brixton uprising.

5 Ultimately,

the summer of 1981 was a pivotal period where the height of resistance action, police brutality, far-right groups, and state legislation coalesced to reveal how the state can depoliticise a mass uprising against racism in Britain.

The media’s depoliticisation of the New Cross Massacre expands beyond 1981, marking the following decades, as acts of racial violence were isolated from the history of anti-immigration legislation, the colonial legacy of the British empire, and right-wing rhetoric on who belongs and does not belong in Britain. We continue to see the murder of Black people in the hands of state authority, whether that be through

state neglect, such as the Grenfell Tower fire in 2011 and higher COVID-19 deaths in Black communities, or

police brutality, including the murders of Stephen Lawrence, Azelle Rodney, Mark Duggan and Chris Kaba, to name only a few.

6 By presenting the timeframe of 1981 to 2022, we aim to combat the ahistoricism that depoliticisation causes. By situating legislation, police violence, and non-state violence in relation to each other, we wish to formulate a pattern of state neglect which crosses over decades whilst documenting the legacy of resistance action and the mobilisation of Black communities to fight against this.

1 Aaron Andrews, “Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: the Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre,” History Workshop Journal 91, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 189.

2 Brenna Bhandar, “Organised State Abandonment: The Meaning of Grenfell,” The Sociological Review, 4 October 2022,

https://thesociologicalreview.org/magazine/october-2022/verticality/organised-state-abandonment/.

3 A. Sivanandan, From Resistance to Rebellion: Asian and Afro-Caribbean Struggles in Britain, (London: The Institute of Race Relations, 1986): 149.

4 Mary Venner, “The disturbances in moss side, Manchester,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 9, no: 3 (2020): 374-377.

5 Venner, 374-377.

6 Bhandar, “Organised State Abandonment”; Denis Campbell, “Racism contributed to disproportionate UK BAME coronavirus deaths, inquiry finds”, The Guardian, 14 June 2020,

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/14/racism-disproportionate-uk-bame-coronavirus-deaths-report; “Family Campaigns,” Inquest, accessed 15 Nov 2022,

https://www.inquest.org.uk/family-campaigns.

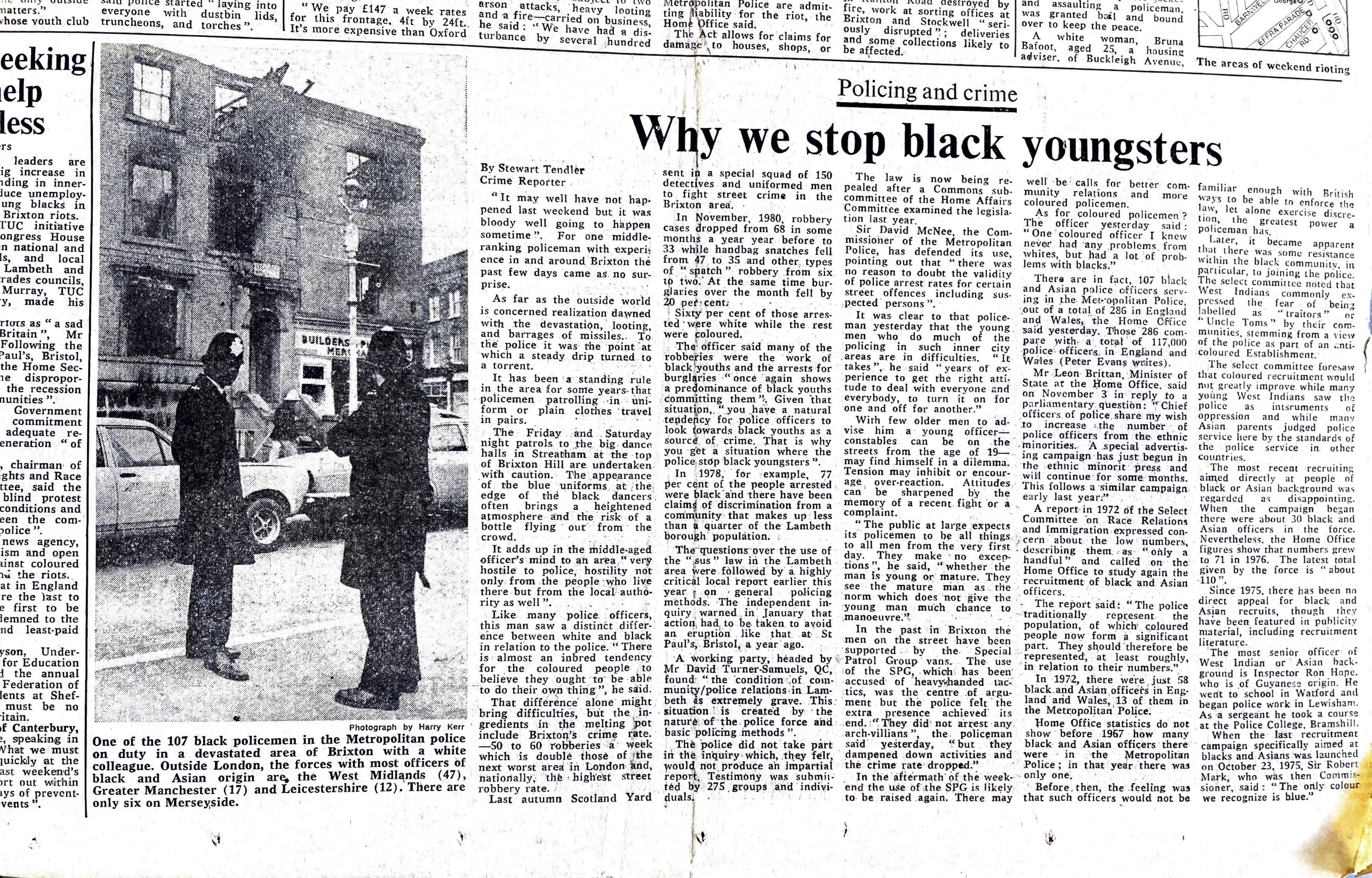

The Times took this pro-police stance further by publishing an article in which the police are given space to justify the targeting of Black teenagers. No such space was afforded to members of the Black community by The Times to share their thoughts on the mishandling of the inquiry.

The Times took this pro-police stance further by publishing an article in which the police are given space to justify the targeting of Black teenagers. No such space was afforded to members of the Black community by The Times to share their thoughts on the mishandling of the inquiry.