Was the police

investigation sufficient?

︎

The police investigation of the New Cross Fire in 1981 is examined across five key case files. Based on evidence collated from different zones of the house, the case files outline key actors, sources, and conclusions drawn from five events related to the New Cross Fire.

These events are all covered extensively by the media. The particular cases are informed by both community attempts to reconstruct the events of the night, as well as in inquests and other state investigations.

Case Files

1. CASE FILE:

INCENDIARY DEVICE

What was the metal device

found in the garden?

2. CASE FILE:

INTRUDER

Who was the unknown person who entered the house with two bags?

3. CASE FILE:

FIGHT THEORY

Was there a fight that

led to

the fire in the front room?

4. CASE FILE: THE SEAT

OF THE FIRE

Did the fire begin by the window or in the centre of the room?

5. CASE FILE: WHITE AUSTIN PRINCESS

Who drove by in a White Austin Princess before the fire?

Much of the evidence used in these case files comes from a draft document recording forensic evidence presented at the inquest, accessed from the George Padmore Institute. These documents show that, at this particular inquest, the police stated that the fire was started when about one pint of inflammable liquid was ignited in the centre of the living room of 439 New Cross Road. The files consist of: the fight theory, the seat of the fire, the incendiary device, the intruder, and the white Austin Princess car.

The case files show, among other things, that the police used coercive interrogation techniques on the witnesses, who would make statements under duress that they would later retract. Our case files also demonstrate that the police and forensic investigators manufactured theories for the fire that they would later withdraw—for example, in the initial theory of the location of the origin of the fire. Each file describes how material passed through different interested parties, was translated or misconstrued in some cases, and indicates that the police often failed to follow due process in their investigation of the case. For example, forensic evidence was altered without explanation between different investigative teams, as in the case of the incendiary device found in the back garden of the house. In another instance of altered evidence, a suspect in a car that drives by the fire is suddenly described as Black, though witnesses agreed he had been a white man. Other discrepancies emerge when we investigate the police investigation, as described below.

The document mentioned above was created by the Fact Finding Commission of the New Cross Massacre Action Committee. Both were set up as part of a meeting called on the 20th January 1981 by Darcus Howe and John La Rose. The meeting was held at the Moonshot Centre, which is situated on the site of the Moonshot Club on Pagnell Street. The meeting was attended by around 300 people. From Howe’s Biography:

‘It heard from the survivors of the fire, discussed the troubled history of the black community in Deptford and addressed the question, as Howe puts it, of ‘what has to be done?.... The immediate aims of the campaign were to establish a Fact Finding Committee which would take statements, gather evidence and oversee the police investigation, and to call a press conference in response to the misleading reports which were beginning to appear in the press’1

The Fact Finding Committee was a way for the survivors and affected community members to respond to the media and to monitor an investigation by a police force with a history of failing to investigate suspected right-wing violence.

‘The Met's failures, particularly when dealing with suspected arson, were legion. The Moonshot Club burnt down in December 1977 a few weeks after reports of it being identified as a target for attack during a local meeting of the National Front. Nonetheless, the police excluded arson as a possible cause (SELM, 16 December 1977). South London Press openly criticized Greenwich Police's decision to rule out foul play when The Albany Theatre in Creek Road, Deptford, burnt down in August 1978. The suspicion that it was an act of arson aimed at a theatre which hosted a number of anti-racist events against the National Front in the run-up to May local elections of that year had increased when a note was received by those who ran the theatre saying ‘Got You! 88’. This was assumed to be from the neo-fascist paramilitary group, Column 88.’2

This left the community with no option but to begin their own counter-investigation in order to present an account of the facts that was not controlled by the police or the media. This history had also left local residents and campaigners with what historian Aaron Andrews calls ‘Experiential Expertise’.3 He uses the example of an exchange between two attendees in this first meeting. “One person was recorded as saying: “A normal petrol bomb could not burn everything up so quickly”, to which another retorted: “must have been a very inflammable spirit”.4 Andrews makes the point that the wider community reacted to the fire was informed by their experience of living in Lewisham — a place with a history of active racist and fascist attacks (see the Battle of Lewisham). Andrews says, “This was a form of expertise rooted in experience rather than technical qualifications – the result of having seen the effects of a “normal petrol bomb” and recognizing that the pace of the blaze at 439 New Cross Road was not “normal”.”5

Andrews also points out that the history that the Fact Finding Commission drew upon for their work still impacted the families of the victims:

The evidence that racist hatred was still a force which threatened physical violence against black Britons was all too current for the families of the victims and leaders of the New Cross Massacre campaign. A series of letters which celebrated the deaths were sent, under the name ‘Brian Bunting, White Man’ and using a false return address, to the parents of the victims. Bunting was believed to be a National Front organiser in Lewisham.6

Results of any investigations into known racist and fascist groups and individuals made during the investigation were hard to come by during our research. The New Cross Massacre Action Committee felt that the police failed in this regard. Lewisham Police Chief Commander John Smith said the letters could have come from the same person or group who started the blaze. There was also an article in The Weekly Herald detailing an anonymous phone call made to them threatening arson attacks and claiming responsibility for the New Cross Fire. The group this caller claimed to represent was Column 88, the same who left a note at the site of the fire at the Albany in Deptford.

1 Robin Bunce and Paul Field, Darcus Howe: A Political Biography (Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472544407. 190.

2 Bunce and Field, Darcus Howe, 191

3 Aaron Andrews, “Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: The Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre,” History Workshop Journal 91, no. 1 (July 27, 2021): 195, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbab010.

4 Andrews, “Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain”, 194

5 Andrews, 194

6 Andrews, 196

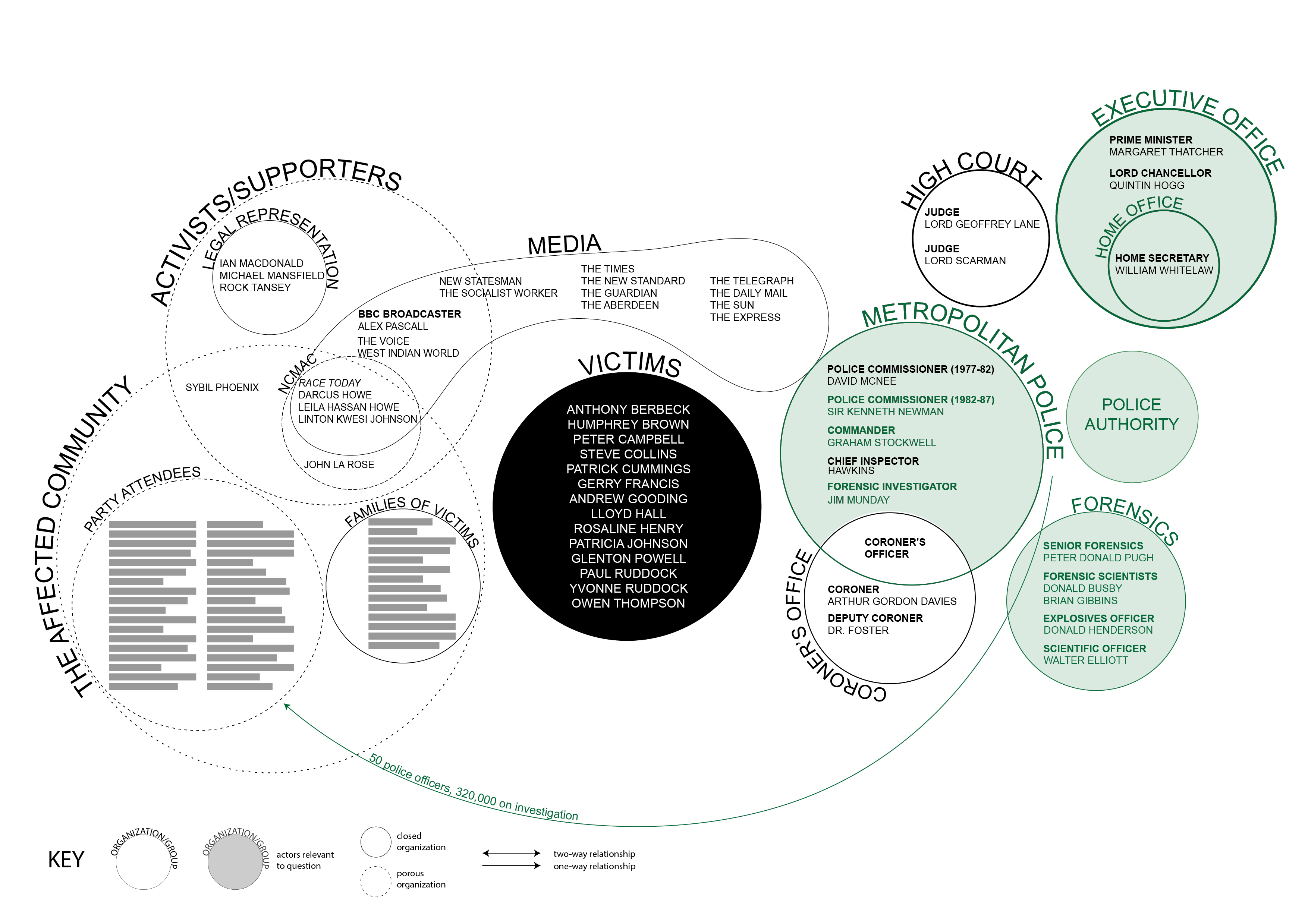

The bubble diagram is a research tool that maps out a complex network of people, organisations, and institutions involved in the New Cross Fire investigation. The visualisation of these relationships is illustrative of alliances and overlaps between organisations.

Each bubble represents a group or institution. Key actors of each group or institution are listed within the bubbles with their current title or position in the time period. The names of party attendees and family members of victims are redacted for privacy reasons. As some individuals and organisations are part of multiple communities or groups, they are shown at the intersection of different bubbles. The borders of each bubble vary between solid and dotted lines to represent its level of transparency and thin or thick lines to represent the relative difficulty (education, class, connections, and other barriers) of joining the group/institution.

The victims are centred within the diagram and represented in inverted colours to show their importance as well as to acknowledge that their agency was taken away. The other bubbles are roughly organised by their direct or indirect relationship to the victims. Organisations with a direct relationship with the victims (like the community and the police) are positioned closer to the victims, while organisations with indirect relationships (like the media) are further away in the drawing. The state institutions are organised vertically to show a chain of command and power.

Through the development of this tool, we found that members of the community often occupied multiple positions as directly affected community members, activists, and those involved in knowledge distribution (media). Members of powerful institutions often played similar, harmful roles in other investigations, for example, Police Commander Graham Stockwell’s record of abuse and Coroner Arthur Gordon Davies’ record of questionable work in inquests.

It is our hope that conceptualising this network can be a valuable way of understanding the distribution of accountability among state institutions as well as the impressive involvement and effort of community groups and organisations in seeking justice and providing care for themselves.

AUTHORS:

Donald Busby (forensic investigator),

Peter Pugh (forensic investigator),

Walter Elliot (scientific officer), Donald Henderson (Scotland Yard)

Donald Busby (forensic investigator),

Peter Pugh (forensic investigator),

Walter Elliot (scientific officer), Donald Henderson (Scotland Yard)

SOURCES:

Information collated from the Fact Finding Commission, which was coordinated by the New Cross Massacre Committee.

Information collated from the Fact Finding Commission, which was coordinated by the New Cross Massacre Committee.

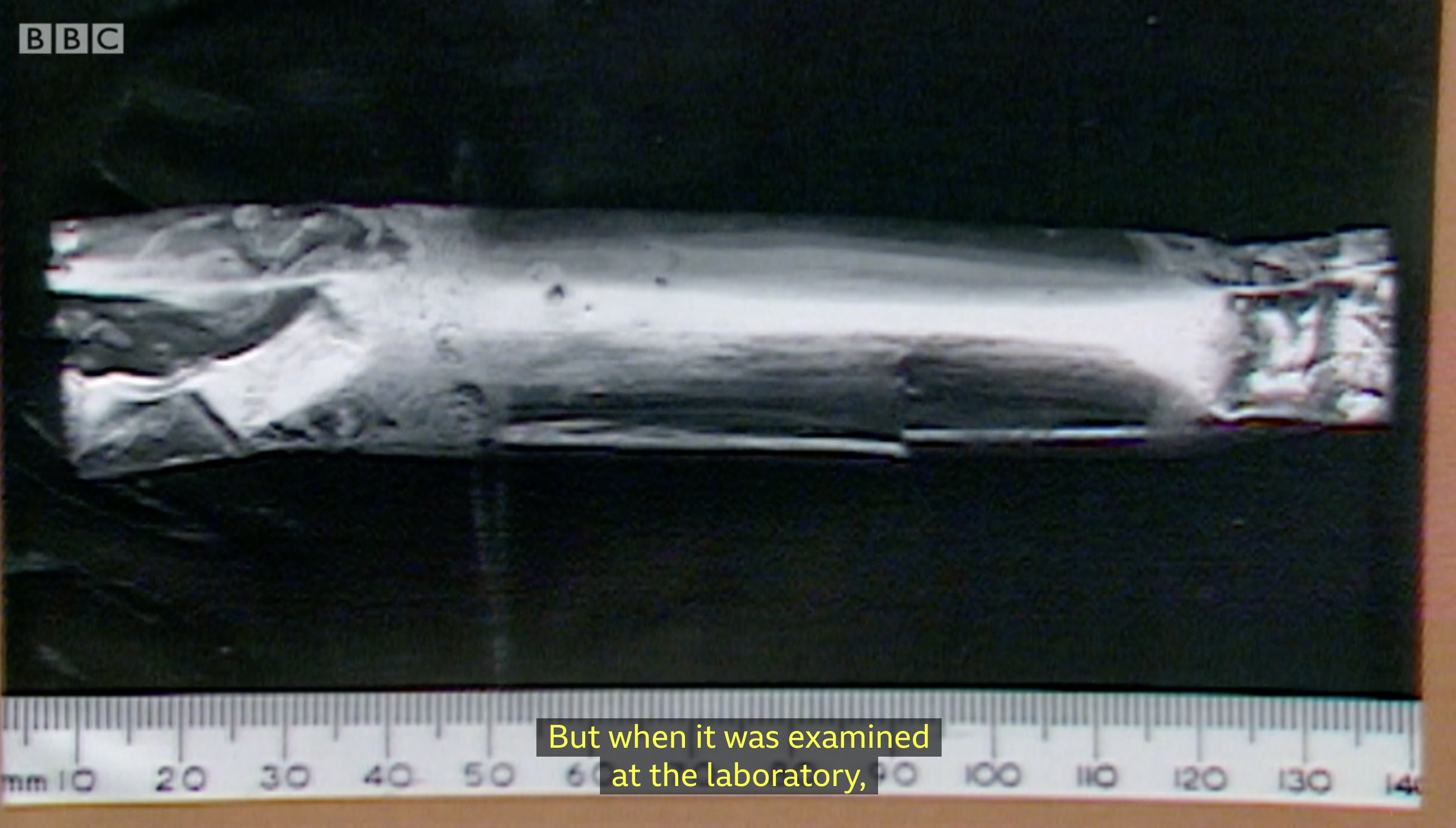

Image: an aluminum tube that looked like a cigar container, holding sugar and chemicals was found in the garden of 439 New Cross Road during the morning after the fire. Chemical tests were conducted by Peter Pugh and presented during the 1981 coroners’ inquest. These indicated the presence of sugar and chlorate. There were signs of combustion, but the tube had not melted. Chlorate and sugar is an incendiary mixture.

Image: A thin-walled aluminium tube approximately 125 mm long and 20 mm in diameter

Donald Henderson, an investigator for Scotland Yard, admitted that he did not look for any wick or container that might be attached to the device. A wick or similar device may have indicated that this object was designed for the purpose of arson.

Image: This image demonstrates that the unidentified object reached Woolwich Explosive Laboratory on March 17 two months after the fire. By then the object had been flattened out into aluminium sheets that are roughly five by two inches.

Strangely, by the time the object reached Walter Elliot, a scientific officer at Woolwich Explosive Laboratory, he found no traces of chlorate or sugar.1

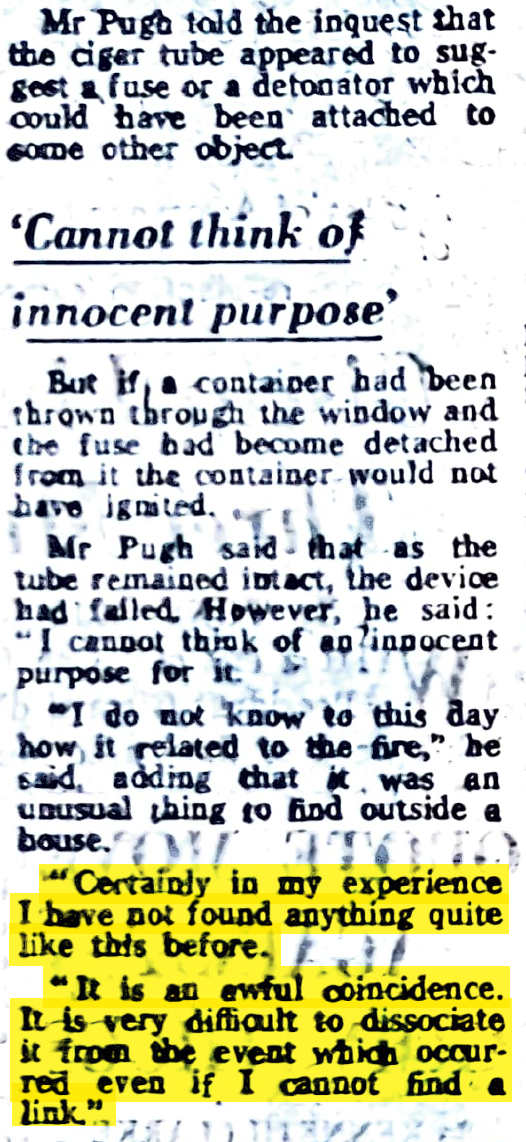

During the inquest Peter Pugh stated, “It is an awful coincidence. It is very difficult to dissociate it from the event which occurred even if I cannot find a link” (The Daily Telegraph, April 22, 1981).

1 Analysis of forensic evidence presented, undated, NCM, NCM 2/3/1/4, New Cross Massacre Campaign 1980-1985, George Padmore institute, Finsbury Park London.

During the inquest Peter Pugh stated, “It is an awful coincidence. It is very difficult to dissociate it from the event which occurred even if I cannot find a link” (The Daily Telegraph, April 22, 1981).

1 Analysis of forensic evidence presented, undated, NCM, NCM 2/3/1/4, New Cross Massacre Campaign 1980-1985, George Padmore institute, Finsbury Park London.

AUTHORS:

Donald Busby (forensic scientist),

John La Rose (activist),

Amza Ruddock (witness),

Peter Pugh (forensic scientist),

John Grieve (Metropolitan Police),

David Blunkett (Home Secretary, June 2001-December 2004)

Donald Busby (forensic scientist),

John La Rose (activist),

Amza Ruddock (witness),

Peter Pugh (forensic scientist),

John Grieve (Metropolitan Police),

David Blunkett (Home Secretary, June 2001-December 2004)

SOURCES:

John LaRose’s typed notes from the New Cross Massacre Campaign’s Application for Judicial Review, specifically the analysis of forensic evidence provided (Feburary 1981);

various articles from the Daily Mirror, Morning Star, and South London Press, among others.

John LaRose’s typed notes from the New Cross Massacre Campaign’s Application for Judicial Review, specifically the analysis of forensic evidence provided (Feburary 1981);

various articles from the Daily Mirror, Morning Star, and South London Press, among others.

CONCLUSIONS:

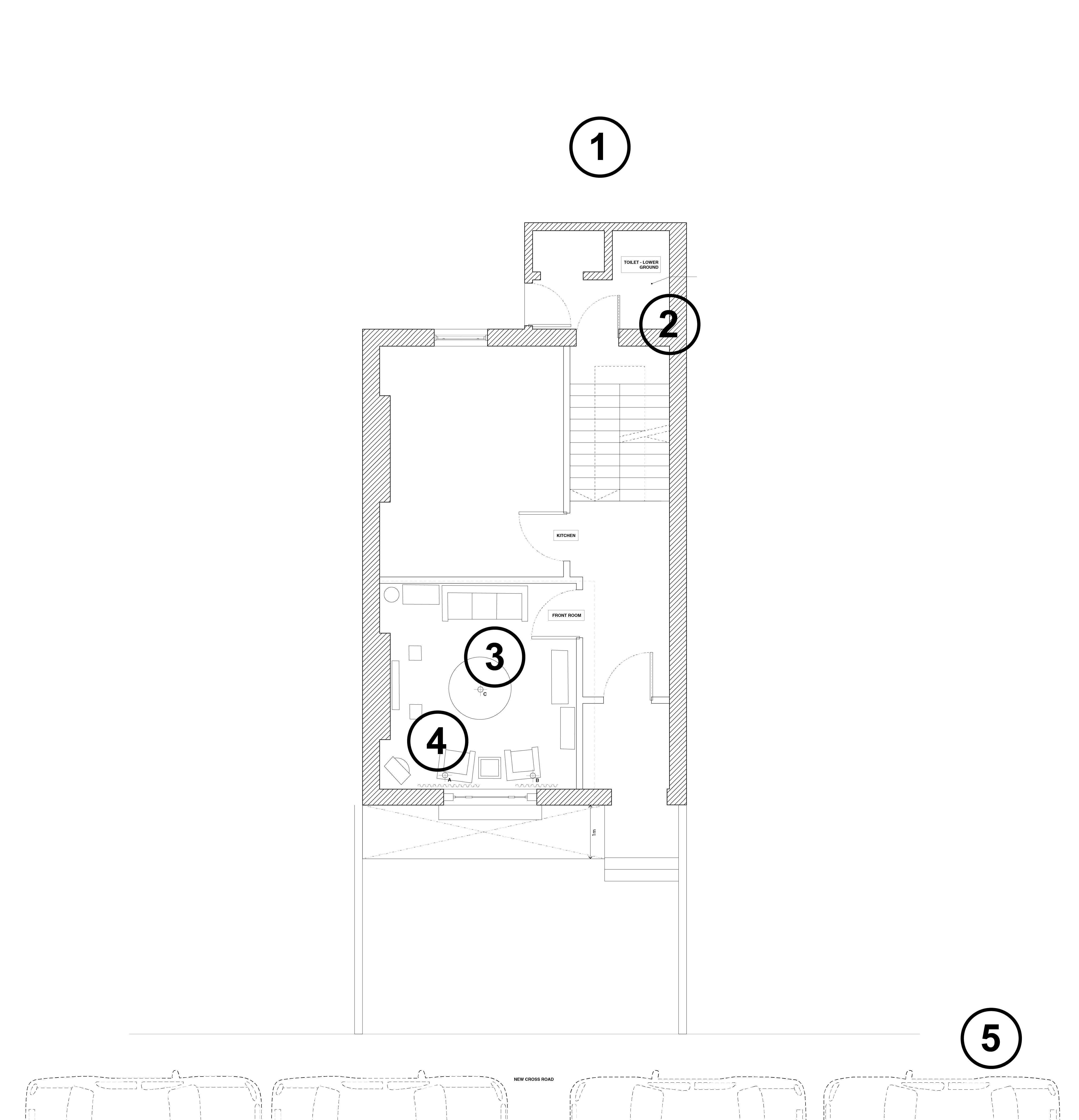

At first, witnesses' statements, media, and police claims considered that an incendiary device landed near the window and started the fire. The fire had thus begun on the chair by the window and then spread to the drapes. After a relatively short time, the police began to state that the fire had started in the centre of the room, and media narratives followed suit, therefore eliminating the possibility of arson. For reasons we could not determine from public resources, the police investigation in 2001 reverted to the original claim of the fire starting next to the window.

EVIDENCE:

In the first few days following the fire, mainstream news publications like the Daily Mirror, as well as the police, cited the possibility of an arson attack:

Detectives who believe the bomb was thrown through a front window, were looking for a coloured man seen sitting outside the house in a white BL Princess. [...] After forensic experts had examined the house, he added: "A liquid substance assisted the spread and intensity of the fire."2

2 Ricketts, Ronald, no title, 19 January 1981, Daily Mirror.

Here is another example from Morning Star two days after the fire:

After a few days, the police narrative shifted away from an arson attack, and much of the media coverage followed suit. By 28 January 1981, the Guardian described the police as not “having discounted a racial attack”, but “they think that as the fire began in the centre of a room, an onslaught by racists is unlikely.” That said, the police “were still examining all possibilities” (South London Press, 3 February 1981).3 Then, by 23 February of the same year, the Guardian reported that the police believed “the fire was begun by someone who was in the house or had sneaked in through the open front door for the time it took to set the fire off.”4 The media stopped reporting extensively on the issue, noted in the Socialist Worker on 21 February 1981, even drawing concern from the police:

3 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

4 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

5 Joanna Rollo, “Why Did They Murder My Children,” Socialist Worker, February 21, 1981, p. 5.

(Even the police are said to be concerned at the way Fleet Street treated the fire.)5

3 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

4 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

5 Joanna Rollo, “Why Did They Murder My Children,” Socialist Worker, February 21, 1981, p. 5.

Subsequently, the media and police narratives both stated that the fire had begun in the centre of the room. The following article predates the inquest by a month yet has already “conclusively” ruled out a racist arson attack. In The Observer published on 22 March 1981:

Police investigating the fire will submit a report to the Director of Public Prosecutions this week. Although it states that the cause remains a mystery, it will conclusively rule out racialist involvement. Police are certain that the fire was started inside the house, but the report leaves open the question whether it was deliberate.

However, members of the local community and survivors who had witnessed the event maintained otherwise. As reported in Socialist Worker:

[The police] tried to smear the one witness who has evidence the fire could have been caused by a firebomb. Mrs Amza Ruddock […] said […] the first things on fire in the front room were the curtains and the chair by the window.6

During the first coroner’s inquest in 1981, Donald Busby and Peter Pugh did a series of forensic tests to determine the origin of the fire.7 Pugh claimed that the attack could not have been arson because the fire started in the center of the room, and it would have been impossible to throw a projectile this far; however, in an earlier map of the fire, Pugh depicted the fire starting by the window. This discrepancy went unexplained.

6 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

7 Analysis of forensic evidence presented, undated, NCM, NCM 2/3/1/4, New cross Massacre Campaign 1980-1985, George Padmore institute, Finsbury Park London.

Image above: Analysis of forensic evidence presented, undated, NCM, NCM 2/3/1/4, New cross Massacre Campaign 1980-1985,

George Padmore institute, Finsbury Park London.

George Padmore institute, Finsbury Park London.

Busby attempted to replicate the introduction of an arson device. He recreated a projectile thrown into the room from the outside via the front window. However, according to La Rose’s notes, Busby did not have the time or resources to recreate this event a sufficient number of times. Busby himself found the conclusions thus anecdotal. In addition, the forensic simulations were only conducted with the drapes and curtains closed, even though eyewitness reports had been mixed on this matter—some witnesses said the drapes were open, and some witnesses stated they were partially open. It is possible that flammable materials could have spread differently had the drapes been open, casting doubts on the legitimacy of Busby’s forensic analysis.

In a letter from John Grieve of the Metropolitan Police to David Blunkett (Home Secretary), in June 2001, it was found that the forensic evidence for the seat of the fire in the centre of room had been insubstantial and definitively began on the chair by the window.8 This conclusion became the basis for the later inquests and investigations in the 2000s.9

8 Aaron Andrews, “Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: The Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre,” History Workshop Journal 91, no. 1 (January 2021): pp. 182-209, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbab010.

9 Kehinde Andrews, “Forty Years on from the New Cross Fire, What Has Changed for Black Britons?,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, January 17, 2021), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/17/forty-years-on-from-the-new-cross-fire-what-has-changed-for-black-britons.

8 Aaron Andrews, “Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: The Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre,” History Workshop Journal 91, no. 1 (January 2021): pp. 182-209, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbab010.

9 Kehinde Andrews, “Forty Years on from the New Cross Fire, What Has Changed for Black Britons?,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, January 17, 2021), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/17/forty-years-on-from-the-new-cross-fire-what-has-changed-for-black-britons.

AUTHORS:

Bob Cox (police spokesperson),

Westindian World (newspaper),

Grass roots (newspaper),

Claudette (witness),

Carl Wright (witness)

Bob Cox (police spokesperson),

Westindian World (newspaper),

Grass roots (newspaper),

Claudette (witness),

Carl Wright (witness)

SOURCES:

Grass Roots,

West Indian World:

Grass Roots,

West Indian World:

CONCLUSION:

There are numerous statements from different witnesses that link the man in the white Austin Princess both spatially and temporally to the start of the fire. However vague that link might be, that man was not considered a suspect by the police. There is no record that further investigation took place to find the owner of the car, nor is there a record of him being considered a suspect.

EVIDENCE:

Bob Cox, a police spokesperson, states, “About five minutes to six a fire broke out quickly. A white saloon car was seen to drive away towards Deptford, do a U-turn with its hazard light still flashing, turned right into Mornington street where it had to brake to avoid another car. We are very interested in finding those two drivers.”10

In another statement made at the end of January 1981, West Indian World wrote, “The police are now looking for the driver of a white Austin Princess and a green Rover car with the letter M in the registration which accelerated very fast from the scene. They are also very anxious to trace a white man with blond hair who was driving a white car with darkened windows which was seen circling the house before the blaze.”11

Claudette, a witness from the party states, "I saw a white guy running into a navy car that was parked near outside the house, he opened the door and drove away fast."12

Between 3:30 and 3:45 am, a blond-haired white man in his early twenties was seen driving up and down in the area of the party (in an old white vehicle, with darkened windows) about five or six times.

Carl Wright stated that while leaving the party and making his way home, he stopped about 100 yards away to wait for his brother, Frank. Carl looked past his brother and saw a figure standing in the middle of the pavement directly in front of the house where the party was being held. “I saw this guy take step towards the house, directly in front of the window; he stepped back and made a throwing movement with his right hand, and simultaneously I heard breaking glass.” According to Carl Wright, this man then walked into an Austin Princess car.13

10 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

11 “£5,000 Reward: For Evidence That Will Lead to the Conviction of the Killers,” West Indian Wolrd, January 30, 1981, p. 1.

12 “New Cross 13 Dead Massacre,” Grassroots Black Community News, March 1981, pp. 1-3. 13 “New Cross 13 Dead Massacre,” Grassroots Black Community News, March 1981, pp. 1-3.

There are numerous statements from different witnesses that link the man in the white Austin Princess both spatially and temporally to the start of the fire. However vague that link might be, that man was not considered a suspect by the police. There is no record that further investigation took place to find the owner of the car, nor is there a record of him being considered a suspect.

EVIDENCE:

Bob Cox, a police spokesperson, states, “About five minutes to six a fire broke out quickly. A white saloon car was seen to drive away towards Deptford, do a U-turn with its hazard light still flashing, turned right into Mornington street where it had to brake to avoid another car. We are very interested in finding those two drivers.”10

In another statement made at the end of January 1981, West Indian World wrote, “The police are now looking for the driver of a white Austin Princess and a green Rover car with the letter M in the registration which accelerated very fast from the scene. They are also very anxious to trace a white man with blond hair who was driving a white car with darkened windows which was seen circling the house before the blaze.”11

Claudette, a witness from the party states, "I saw a white guy running into a navy car that was parked near outside the house, he opened the door and drove away fast."12

Between 3:30 and 3:45 am, a blond-haired white man in his early twenties was seen driving up and down in the area of the party (in an old white vehicle, with darkened windows) about five or six times.

Carl Wright stated that while leaving the party and making his way home, he stopped about 100 yards away to wait for his brother, Frank. Carl looked past his brother and saw a figure standing in the middle of the pavement directly in front of the house where the party was being held. “I saw this guy take step towards the house, directly in front of the window; he stepped back and made a throwing movement with his right hand, and simultaneously I heard breaking glass.” According to Carl Wright, this man then walked into an Austin Princess car.13

10 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

11 “£5,000 Reward: For Evidence That Will Lead to the Conviction of the Killers,” West Indian Wolrd, January 30, 1981, p. 1.

12 “New Cross 13 Dead Massacre,” Grassroots Black Community News, March 1981, pp. 1-3. 13 “New Cross 13 Dead Massacre,” Grassroots Black Community News, March 1981, pp. 1-3.

AUTHORS:

Donald Busby,

Socialist Worker editorial,

John La Rose

Donald Busby,

Socialist Worker editorial,

John La Rose

SOURCES:

Fact Finding Meeting’s document, ‘The Woman with Suitcase and Bag’; Socialist Worker; The Times and other publications.

Fact Finding Meeting’s document, ‘The Woman with Suitcase and Bag’; Socialist Worker; The Times and other publications.

CONCLUSIONS:

A woman was seen entering the house party with two bags. She went into the basement and then re-emerged. Police concluded she was not a suspect.

EVIDENCE:

After the fire, many witnesses testified to having seen a woman enter the party shortly before the fire broke out. This event was later reported in the Fact Finding Commission, which was established by the New Cross Massacre Action Committee to aggregate evidence from survivors. The FFC wrote:

“There is a report going around and this is substantiated by several people who were at the party that a white woman about 22-23 years of age dressed in a jeans with blonde hair, entered the house shortly before the fire and asked whose party it was. She then proceeded downstairs where the toilets are and was seen there by several people. When she entered the house she was carrying a bag and a suitcase. She subsequently left the house. There are not many people who could say for sure that she had or did not have the suitcase or bag.”

A woman was seen entering the house party with two bags. She went into the basement and then re-emerged. Police concluded she was not a suspect.

EVIDENCE:

After the fire, many witnesses testified to having seen a woman enter the party shortly before the fire broke out. This event was later reported in the Fact Finding Commission, which was established by the New Cross Massacre Action Committee to aggregate evidence from survivors. The FFC wrote:

“There is a report going around and this is substantiated by several people who were at the party that a white woman about 22-23 years of age dressed in a jeans with blonde hair, entered the house shortly before the fire and asked whose party it was. She then proceeded downstairs where the toilets are and was seen there by several people. When she entered the house she was carrying a bag and a suitcase. She subsequently left the house. There are not many people who could say for sure that she had or did not have the suitcase or bag.”

'The Woman with Suitcase and Bag': 21 January 1981, NCM 2/1/1/1/6,

George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

The woman was spotted by Angella and Marlene, two partygoers, at around 4:45, according to an undated newspaper clipping from archives of the George Padmore Institute.14 Angella and Marlene found her suspicious, and she was seen an hour later speaking to the police after the house was engulfed in flames.15

It is not clear how or why she was dismissed as a suspect immediately at the scene, beyond perhaps that she had been seen to wander into unknown parties before under false pretenses.16

14 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

15 Grassroots. “New Cross 13 Dead Massacre.” Grassroots Black Community News. March 1981.

16 Grassroots. “New Cross 13 Dead Massacre.”,1981.

It is not clear how or why she was dismissed as a suspect immediately at the scene, beyond perhaps that she had been seen to wander into unknown parties before under false pretenses.16

14 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

15 Grassroots. “New Cross 13 Dead Massacre.” Grassroots Black Community News. March 1981.

16 Grassroots. “New Cross 13 Dead Massacre.”,1981.

AUTHORS:

Wayne Downer (witness),

Carl Wright (witness),

Amza Ruddock (witness),

Denis Gooding (witness), Graham Stockwell (police commander).

Wayne Downer (witness),

Carl Wright (witness),

Amza Ruddock (witness),

Denis Gooding (witness), Graham Stockwell (police commander).

SOURCES:

Various newspaper clippings from 1981 until 2021 such as New Standard – April 23, 1981 – “’Quarrel but no fight’ at the party” and The Guardian, 30 April 1981; “Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: the Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre” by Aaron Andrews (June 2021)

Various newspaper clippings from 1981 until 2021 such as New Standard – April 23, 1981 – “’Quarrel but no fight’ at the party” and The Guardian, 30 April 1981; “Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: the Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre” by Aaron Andrews (June 2021)

CONCLUSIONS:

The police established the narrative of the fire's inception beginning in the centre of the room. The police examined the theory that a fight had broken out during the party that led to the fire.

This narrative was unsubstantiated by witness claims. However, some witnesses under coerced interrogation techniques claimed to have seen the fire start from the centre of the room. Later, the police dismissed the fight theory for unclear reasons.

EVIDENCE:

Police began to investigate the theory that a fight had broken out in the front room, and that this fight had led to a fire starting in the centre of the room. Commander Graham Stockwell said there had been reports of a fight at the party and that the party had many gatecrashers.

Publicly, the police claimed two different stories. The first was that there was a fight in the front room that involved a glass table being smashed, which explained the origin of the glass, and then that the front room was robbed. In order to cover up the crime, the room was set on fire. Evidence cited by the police included the cut up pillows. However, Mrs. Ruddock later stated in court that her pouffes in the front room had “been damaged for a long time” and were not cut up as the result of a fight.17

The police also claimed that the fight had been between two romantic rivals, which had spilled into the front room, though the front room had been off-limits to the young people at the party. Mrs. Ruddock reported that the fight theory was “totally untrue.”18 Many of the adults had been sitting in the kitchen, and they would have heard a fight in the front room which was only separated from the kitchen by a thin board.

17 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London

18 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute

The police established the narrative of the fire's inception beginning in the centre of the room. The police examined the theory that a fight had broken out during the party that led to the fire.

This narrative was unsubstantiated by witness claims. However, some witnesses under coerced interrogation techniques claimed to have seen the fire start from the centre of the room. Later, the police dismissed the fight theory for unclear reasons.

EVIDENCE:

Police began to investigate the theory that a fight had broken out in the front room, and that this fight had led to a fire starting in the centre of the room. Commander Graham Stockwell said there had been reports of a fight at the party and that the party had many gatecrashers.

Publicly, the police claimed two different stories. The first was that there was a fight in the front room that involved a glass table being smashed, which explained the origin of the glass, and then that the front room was robbed. In order to cover up the crime, the room was set on fire. Evidence cited by the police included the cut up pillows. However, Mrs. Ruddock later stated in court that her pouffes in the front room had “been damaged for a long time” and were not cut up as the result of a fight.17

The police also claimed that the fight had been between two romantic rivals, which had spilled into the front room, though the front room had been off-limits to the young people at the party. Mrs. Ruddock reported that the fight theory was “totally untrue.”18 Many of the adults had been sitting in the kitchen, and they would have heard a fight in the front room which was only separated from the kitchen by a thin board.

17 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London

18 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute

Audley Forbes […] heard three or four people having an argument in the hallway outside, but he told coroner Dr Arthur Gordon Davies, that although the voices he heard were raised, it sounded like a friendly argument and definitely not a fight.

Mr. [Andrew] Hastings[...] said that as far as he knew he was the last person in the front room before the fire. It was around 5.30 and there were six girls in the room talking about what time the tubes start and how they were going to get home. Then they left. As he left the room to go into the kitchen he noticed there were three people in the hallway talking.1 9

Denise Gooding was an 11-year-old who attended the party that night. The police interrogated her immediately after she was released from the hospital without adult supervision. The police coerced her into claiming she had overheard a fight. She stated she was “kept in the police station for hours and hours and hours one night, just being questioned and questioned.”20 Others also reported that they were coerced into stating they had overheard parts of a fight.

Carl Wright was another partygoer who found that his evidence and statements were used by the police to ‘prove’ that the fire had not been an arson attack. Darcus Howe, an activist, later stated that “[w]e were able to track the police investigation and discovered very quickly that they were forcing statements out of those who attended the party without lawyers or parents present.”

Another witness, Wayne Downer, also stated to the media that he had been kept in a cell for two nights. Under threats that the police would prosecute him for a different offense, he made a statement that he and some other boys had vandalized the front room, kicking over a “dieselish” liquid onto the floor. He added that one of the children who died in the fire had said, “Let’s set fire to the room.” Downer later retracted this story, explaining how he invented it to appease the police.

19 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

20 Aaron Andrews, “Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: The Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre,” History Workshop Journal 91, no. 1 (January 2021): pp. 182-209, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbab010.

As reported in The Sun on 29 April 1981:

Oleander Agbetu, who was not at the party but lost friends to it, stated to The Mirror in 2021:

The fight theory was eventually dismissed by the police, presumably due the overwhelming witness testimony to the contrary.

21 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

[Downer] claimed been "forced" to sign it. Dr Davies asked him Why be signed. Downer said: “A policeman came to my house. When we reached the police station, he showed me a statement of another witness for another court case and said he would be willing to forget this if I told them what they wanted to know” Dr Davies asked: “You are saying the police literally blackmailed you into making a statement. They threatened you with another case” Downer replied “Yes.” Dr Davies: “So the whole 70 pages of statements are a pack of lies made up by the police?” Downer: “No. All I am saying is what they were telling me - not asking me.”21

Oleander Agbetu, who was not at the party but lost friends to it, stated to The Mirror in 2021:

I’m not saying it’s a racist attack but the way the police handled it was racist. Families were treated as suspects and they weren’t interested in finding the perpetrators. If it was a group of white young people who had perished in a fire like this they would have found out who was behind it. We were not taken seriously as a community.

The fight theory was eventually dismissed by the police, presumably due the overwhelming witness testimony to the contrary.

21 Newspapers and newspaper cuttings: Jan-Apr 1981, March 1981, NCM, NCM 4/1/1, George Padmore Institute, Finsbury Park London.

Results of any investigations into known racist and fascist groups and individuals made during the investigation were hard to come by during our research. It was felt by the New Cross Massacre Action Committee that the police failed in this regard. Lewisham police chief commander John Smith said the racist letters sent to the families of the victims soon after the fire could have come from the same person or group who started the blaze. There was also an article in the Weekly Herald detailing an anonymous phone call made to them threatening arson attacks and claiming responsibility for the New Cross fire. The group this caller claimed to represent was Column 88, the same who left a note at the site of the fire at the Albany in Deptford.

The Met’s Special Branch, which at the time was the department that dealt with extremist groups and hate crimes, was brought into the investigation on the 29th of January, 11 days after the fire.