![]()

The

bubble diagram is a research tool that maps out a complex network of

people, organisations, and institutions involved in the New Cross Fire investigation. The visualisation of these relationships is illustrative of alliances and overlaps between organisations.

Each bubble represents a group or institution. Key actors of each group or institution are listed within the bubbles with their current title or position in the time period. The names of party attendees and family members of victims are redacted for privacy reasons. As some individuals and organisations are part of multiple communities or groups, they are shown at the

intersection of different bubbles. The

borders of each bubble vary between solid and dotted lines to represent its level of transparency and thin or thick lines to represent the relative difficulty (education, class, connections, and other barriers) of joining the group/institution.

The victims are centred within the diagram and represented in inverted colors to show their importance as well as to acknowledge that their agency was taken away. The other bubbles are roughly organised by their direct or indirect relationship to the victims. Organisations with a direct relationship with the victims (like the community and the police) are positioned closer to the victims, while organisations with indirect relationships (like the media) are further away in the drawing. The state institutions are

organised vertically to show a chain of command and power.

Through the development of this tool, we found that

members of the community often occupied multiple positions as directly affected community members, activists, and those involved in knowledge distribution (media).

Members of powerful institutions often played similar, harmful roles in other investigations, for example, Police Commander Graham Stockwell’s record of abuse and Coroner Arthur Gordon Davies’ record of questionable work in inquests.

It is our hope that conceptualising this network can be a valuable way of

understanding the distribution of accountability among state institutions as well as the

impressive involvement and effort of community groups and organisations in seeking justice and providing care for themselves.

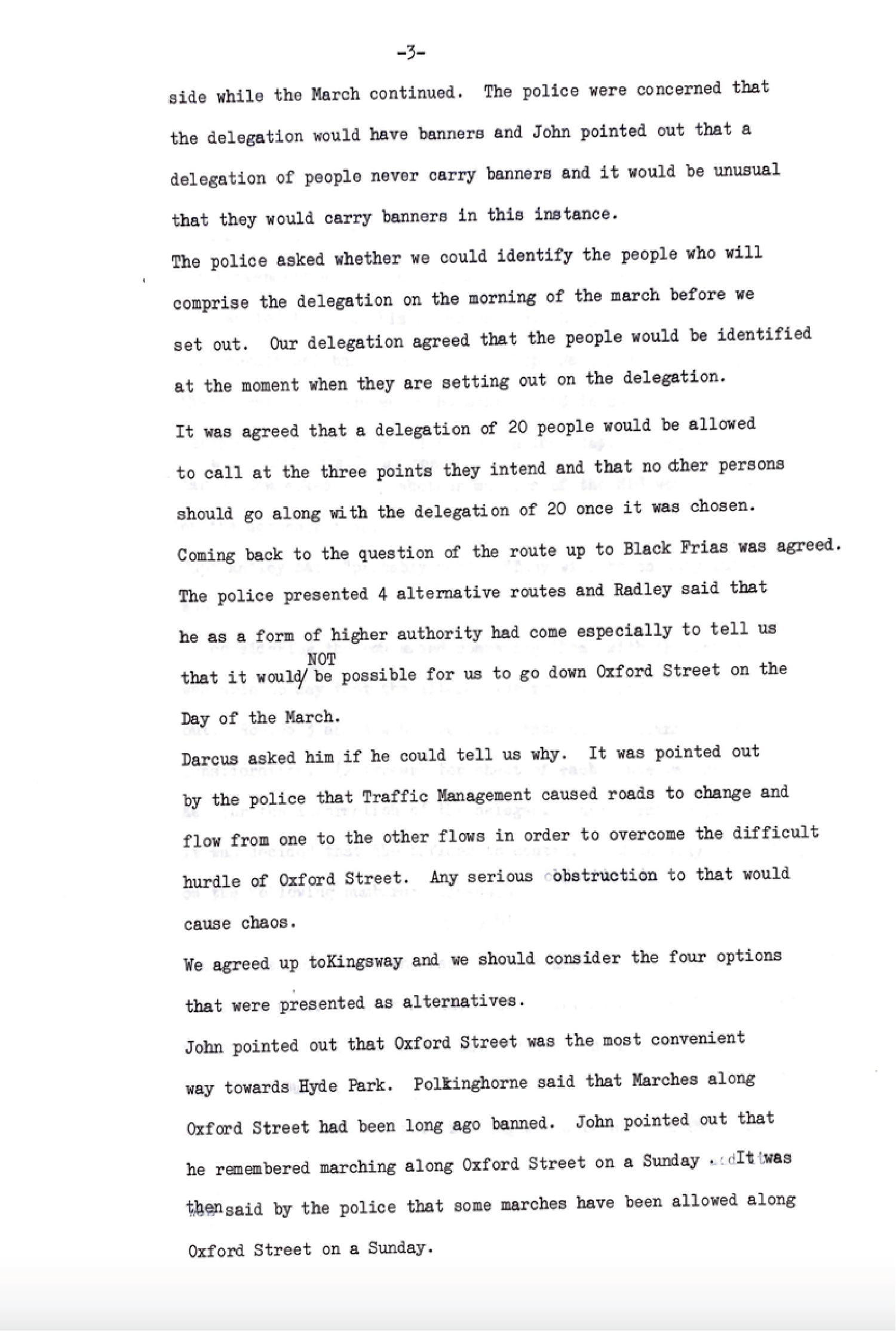

All 6 following pictures: George Padmore Institute (GPI), NCM 2/2/2/12

I don't think I saw Owen in the passageway.

I told them I did.

I was told I had a court case coming up.

I had no choice.

I wasn’t asked those questions, I was told the questions.

Most of the answers were untrue.

I wasn’t asked, I was told.

They threatened me with another case.

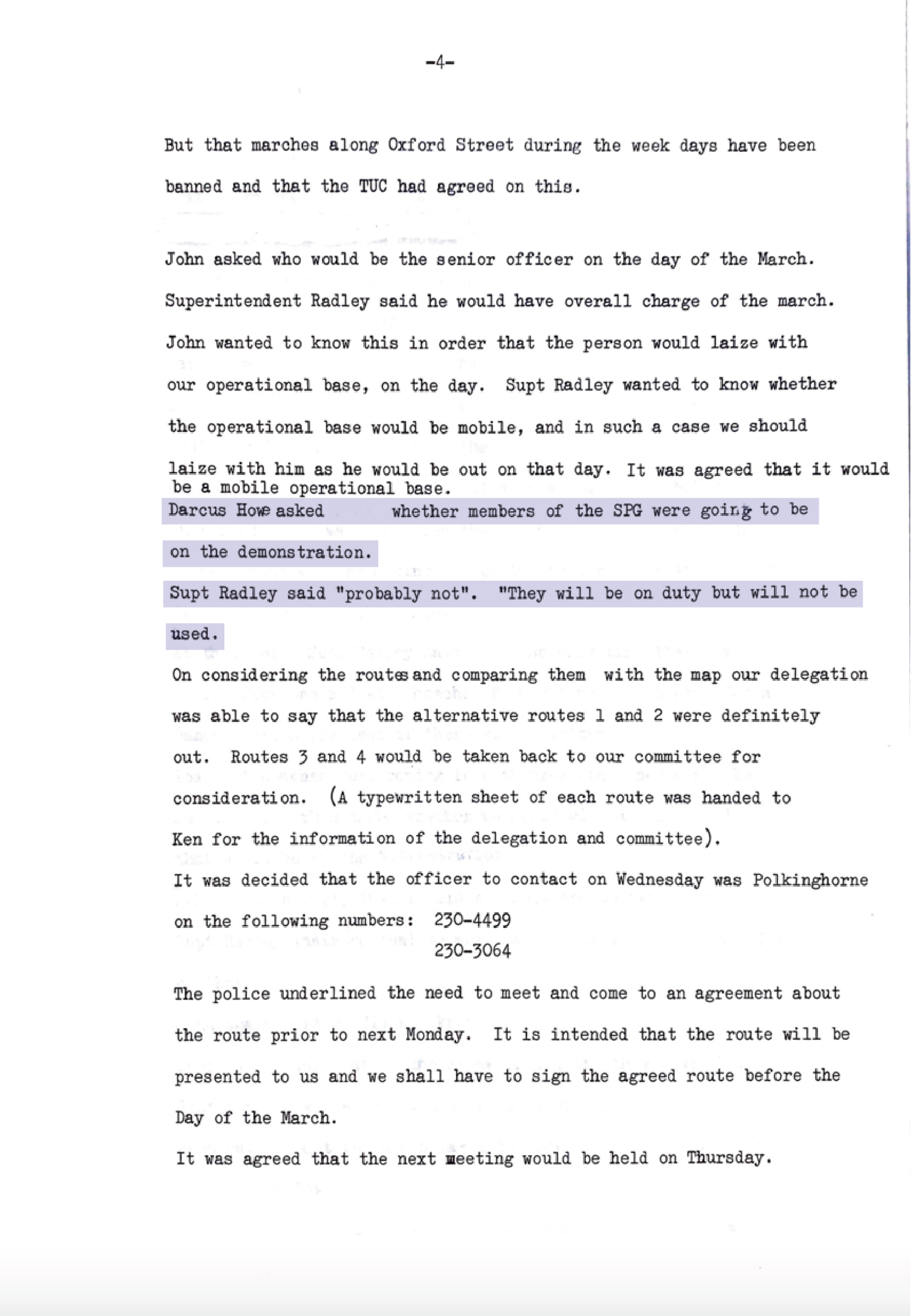

They put me in a cell in Greenwich.

Were you worried? Yes.

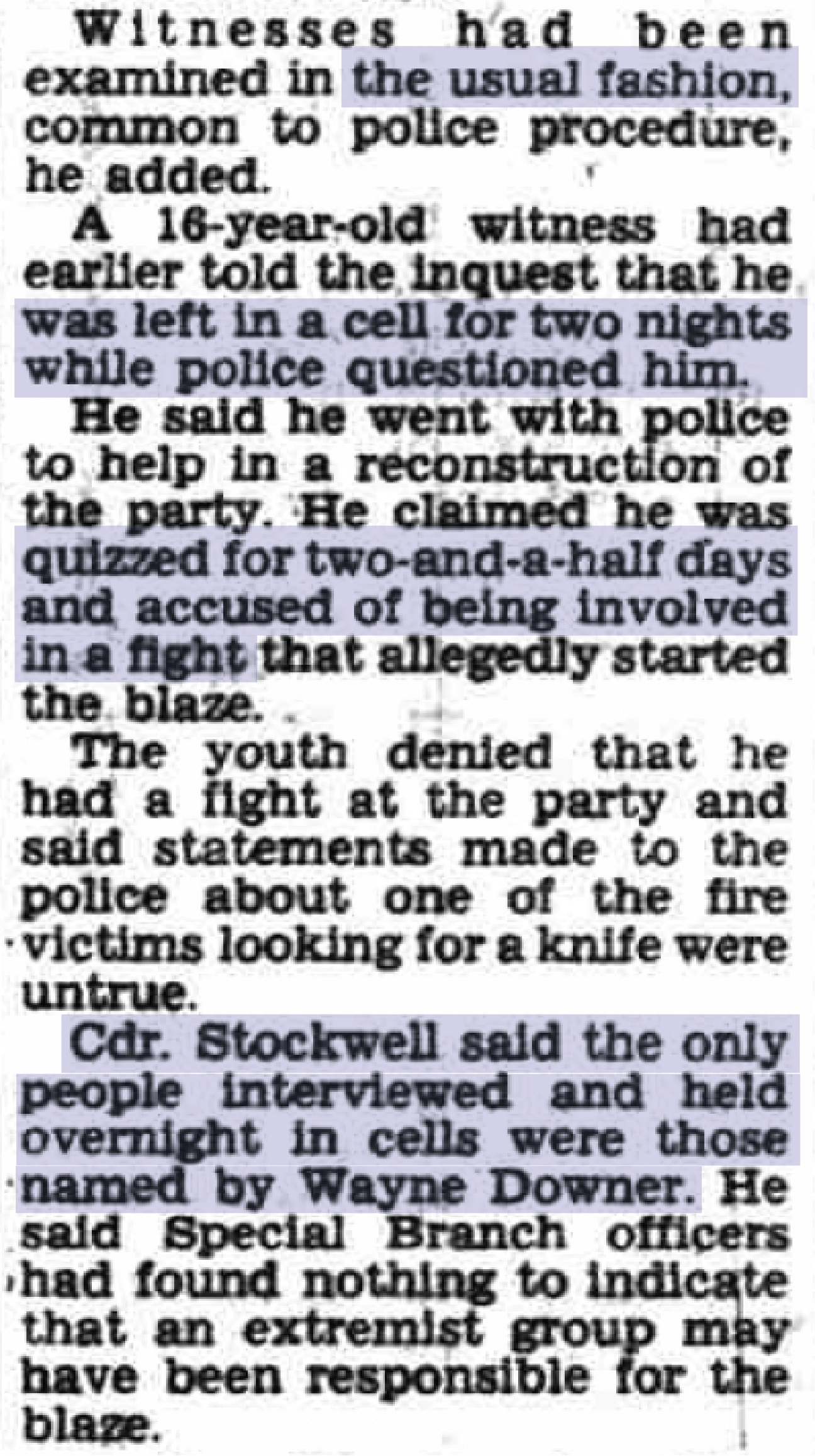

Police, under the direction of lead investigator Commander Graham Stockwell, interrogated the children present at the New Cross Fire using

extreme and coercive means.

Excerpts from John La Rose's handwritten notes from the 1981 Inquest demonstrate the threatening nature of police questioning as recalled by Wayne Downer. Downer, who was a teen at the time, describes being threatened with other charges, held in a cell, and forced to assent to the police's account.

The following coercive methods of interrogation were used to produce the police's false theory of

a fight breaking out and starting the fire.

Wayne Downer's

coerced testimony was used to name six key witnesses, including himself, from which the police extracted additional coerced statements to build

the false narrative of the fight.

National Archives, New Cross Fire High Court Decision on Reopening Inquest

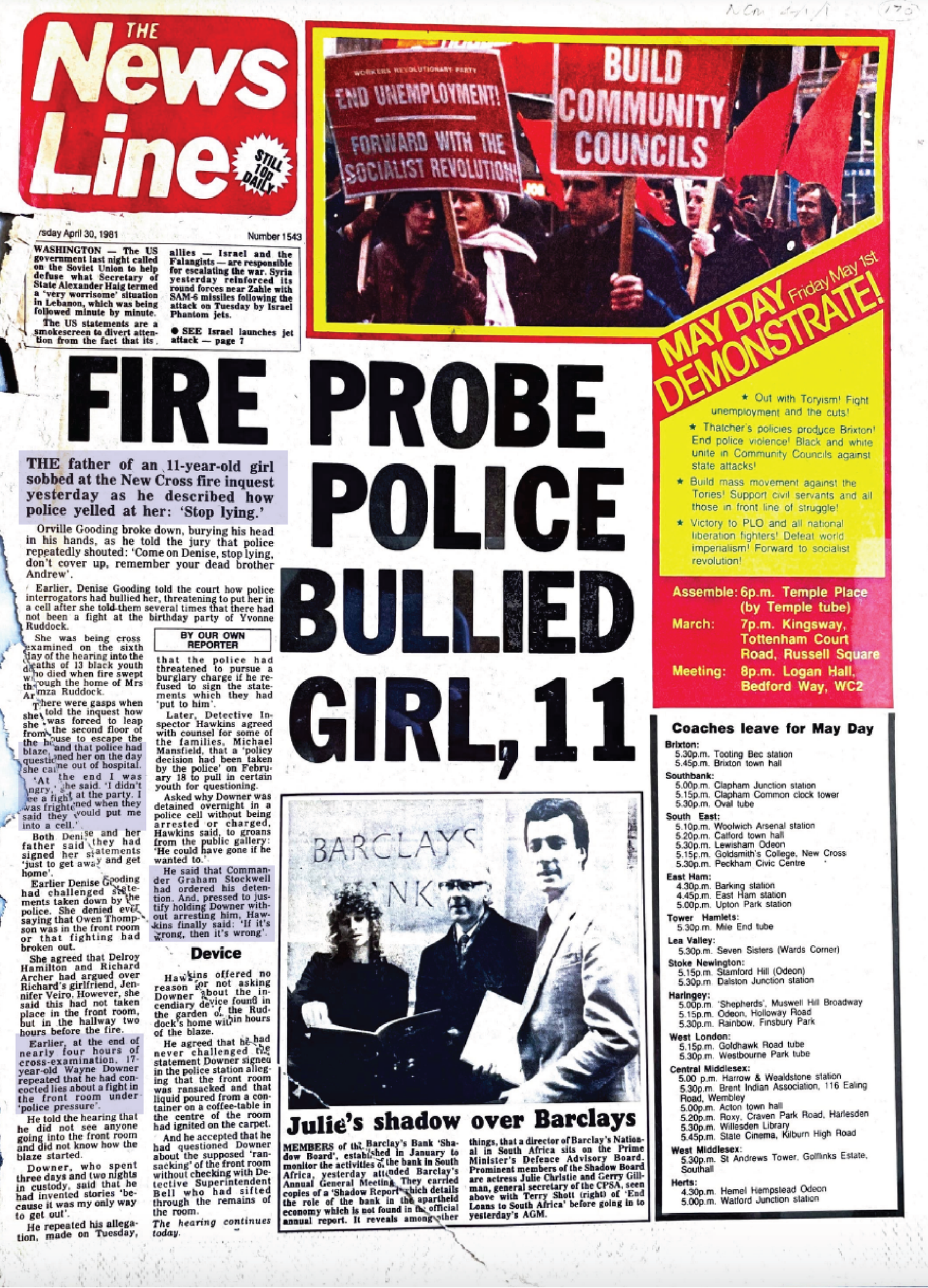

Errol Leiba, one of the key witnesses, was detained overnight for questioning. Another unnamed witness was "left in a cell for two nights while police questioned him." In Aberdeen Press and Journal, Stockwell labeled these practices as "the usual fashion" of police investigation procedure.

Police also aggressively questioned Denise Gooding (age 11) on the day she was released from the hospital for injuries sustained in the fire and her escape through the second-floor window.

GPI, NCM 4/1/1

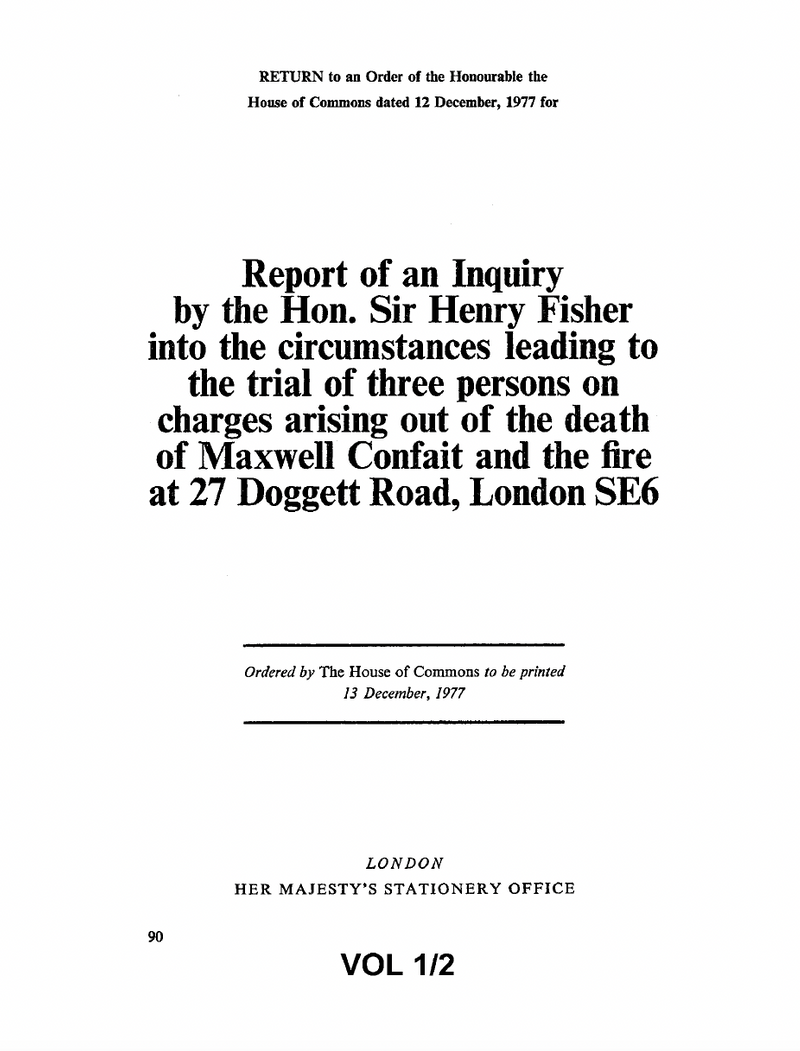

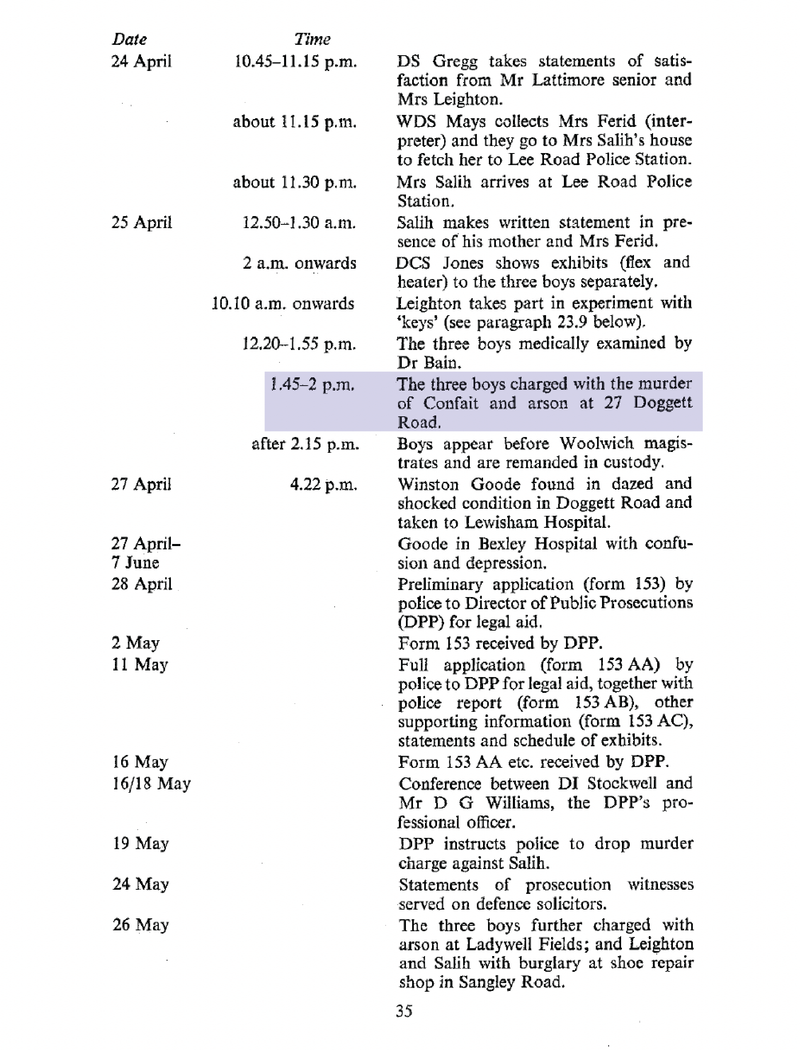

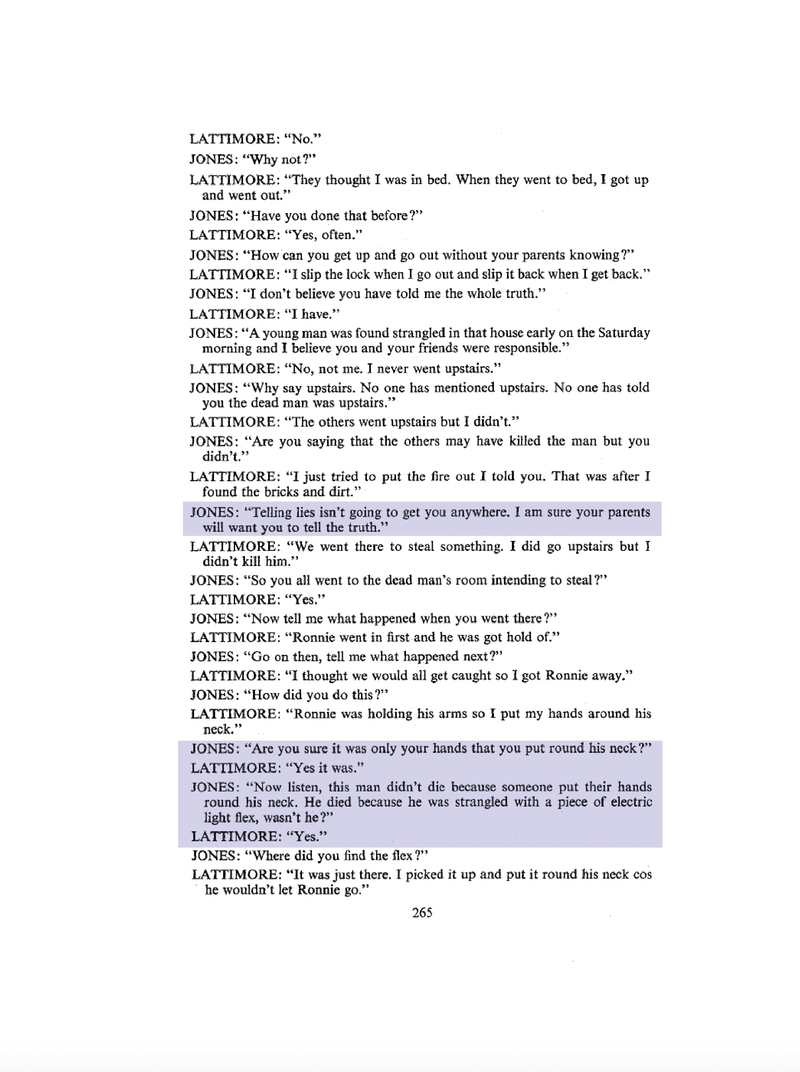

Commander Stockwell had a history of abusing his power in questioning witnesses, specifically unaccompanied teenagers. On 22 April 1972, Michelle Confait, a transgender woman, was murdered in her South East London flat, which was later burnt down.1 Stockwell, then Detective Inspector of the local CID, and Detective Chief Superintendent Alan Jones interrogated three teenagers without adult supervision, legal counsel, or a tape recording.2

1 Robin Bunce and Paul Field. “Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said” in Darcus Howe: A Political Biography, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2014), 197. Andrews, Aaron, ‘Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: The Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre’, History Workshop Journal, 91.1 (2021), 197

2 Andrews, Aaron, ‘Truth, Justice, and Expertise in 1980s Britain: The Cultural Politics of the New Cross Massacre’, History Workshop Journal, 91.1 (2021), 197.

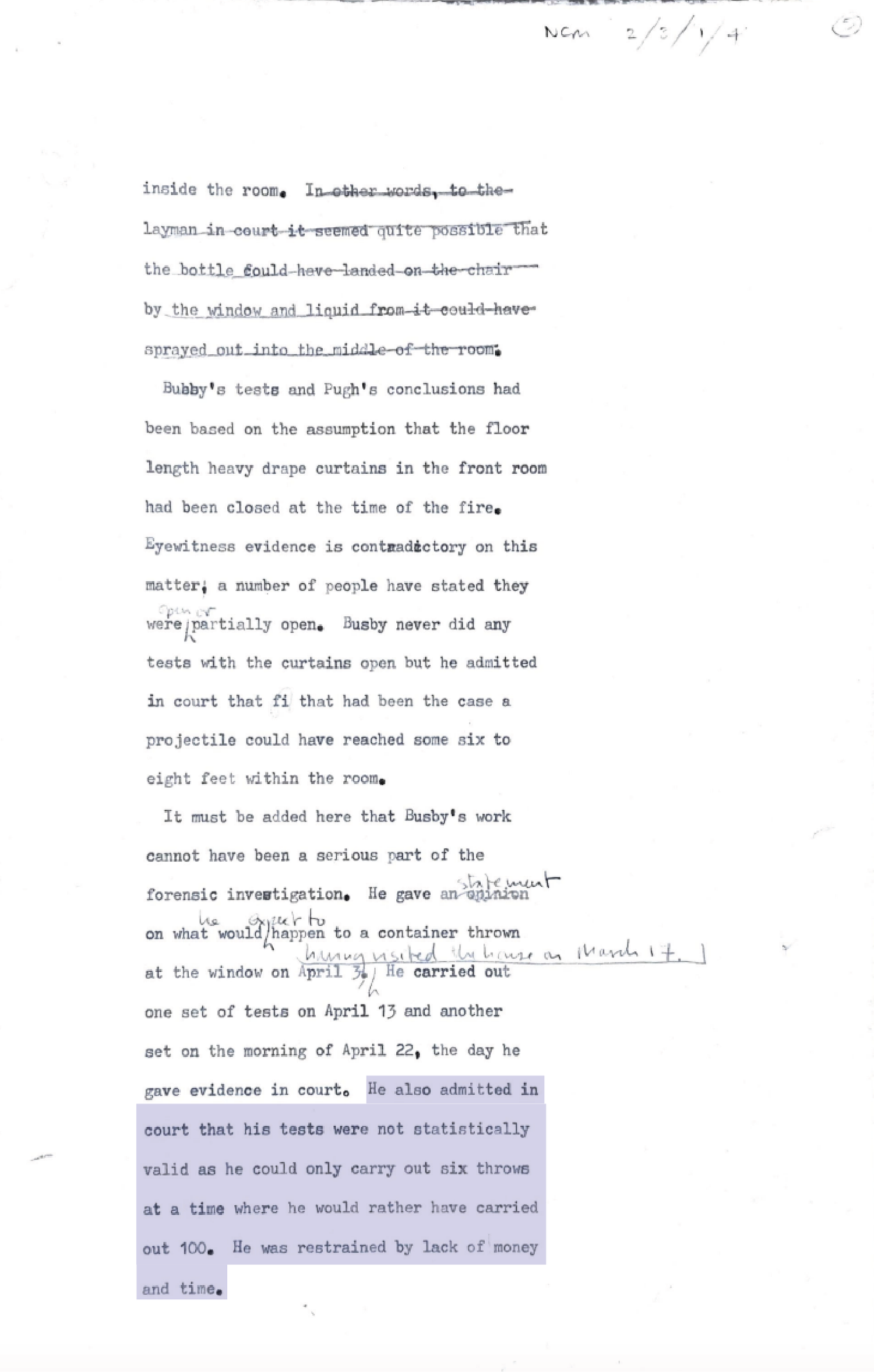

All 3 pictures: Henry Fisher. “Report of an inquiry into the death of Maxwell Confait.”

Home Office. December 14, 1997, 265 and 35.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-an-inquiry-into-the-death-of-maxwell-confait

These teens were Colin Lattimore (18), Ronnie Leighton (15), and Ahmet Salih (14). With prompting and leading questioning from the police, two of the boys confessed to the murder of Confait, and all three confessed to burning Confait’s home.

3 Three years later, the teens were later exonerated through unequivocal alibis that were corroborated by the forensic timeline of the murder.

4 They had been

falsely convicted.

The Fisher Report later revealed that, after obtaining the confessions,

the police directed the investigation such that “enquiries continued only to strengthen the evidence against [the young men].”

5 They did not pursue other leads. Within three days the case was marked as “closed.”

6 When the investigation materials were passed to the prosecution for trial, information was simplified, omitted, or transformed to mask inconsistencies and artificially strengthen the police’s shoehorned account.

7

Importantly, the release of the boys occurred six years before Stockwell was brought onto the New Cross Fire investigation.

Stockwell was specifically sought for this case despite his history and, according to some, because of it.

3 Henry Fisher. “Report of an inquiry into the death of Maxwell Confait.” Home Office. December 12, 1977, 265.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-an-inquiry-into-the-death-of-maxwell-confait.

4 Henry Fisher. “Report of an inquiry into the death of Maxwell Confait.” Home Office. December 12, 1977, 38.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-an-inquiry-into-the-death-of-maxwell-confait.

5 Henry Fisher. “Report of an inquiry into the death of Maxwell Confait.” Home Office. December 12, 1977, 203.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-an-inquiry-into-the-death-of-maxwell-confait

6 Henry Fisher. “Report of an inquiry into the death of Maxwell Confait.” Home Office. December 124, 19977, 20.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-an-inquiry-into-the-death-of-maxwell-confait

7 Doreen McBarnet. "The Fisher Report on the Confait Case: Four Issues." Modern Law Review 41, no. 4 (1978): 455-6.

Image: Robin Bunce and Paul Field. “Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said” in Darcus Howe: A Political Biography, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2014), 193

Two years prior, in 1970, Stockwell was "instrumental in reinstating the incitement to riot charges against the Mangrove Nine."8

In Darcus Howe's biography by Robin Bunce and Paul Field, Howe stated that Stockwell's involvement in the New Cross Fire Investigation was likely because "he knew some of the characters in the game" from Mangrove.9

Despite his misconduct in both the Confait case and the New Cross Massacre, Graham Stockwell was

rewarded with promotions. After serving as the South London head of CID, he was promoted to Head of the Flying Squad and the Regional Crime Squads.

10 Moreover, he later served as the Metropolitan Police Commander of the Metropolitan and City of London Company Fraud Department.

11 Between 1984 and 1992, Stockwell worked in Hong Kong as the Deputy Commissioner of the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC).

12 In this role, he also engaged in anti-corruption work in Botswana beginning in 1992 as the Director of the Directorate on Commission and Economic Crime (DCEC).

13

8 Robin Bunce and Paul Field. “Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said” in Darcus Howe: A Political Biography, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2014), 193.

9 Robin Bunce and Paul Field. “Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said” in Darcus Howe: A Political Biography, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2014), 193.

10 Graham Stockwell, “Graham Stockwell,” interview by Gabriel Kuris, Princeton University: Innovations for Successful Societies, August 12, 2013, 1. https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/sites/successfulsocieties/files/interviews/transcripts/3556/graham_stockwell.pdf.

11 Graham Stockwell, “Graham Stockwell,” interview by Gabriel Kuris, Princeton University: Innovations for Successful Societies, August 12, 2013, 1. https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/sites/successfulsocieties/files/interviews/transcripts/3556/graham_stockwell.pdf.

12 Graham Stockwell, “Graham Stockwell,” interview by Gabriel Kuris, Princeton University: Innovations for Successful Societies, August 12, 2013, 1. https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/sites/successfulsocieties/files/interviews/transcripts/3556/graham_stockwell.pdf.

13 Graham Stockwell, “Graham Stockwell,” interview by Gabriel Kuris, Princeton University: Innovations for Successful Societies, August 12, 2013, 2. https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/sites/successfulsocieties/files/interviews/transcripts/3556/graham_stockwell.pdf.

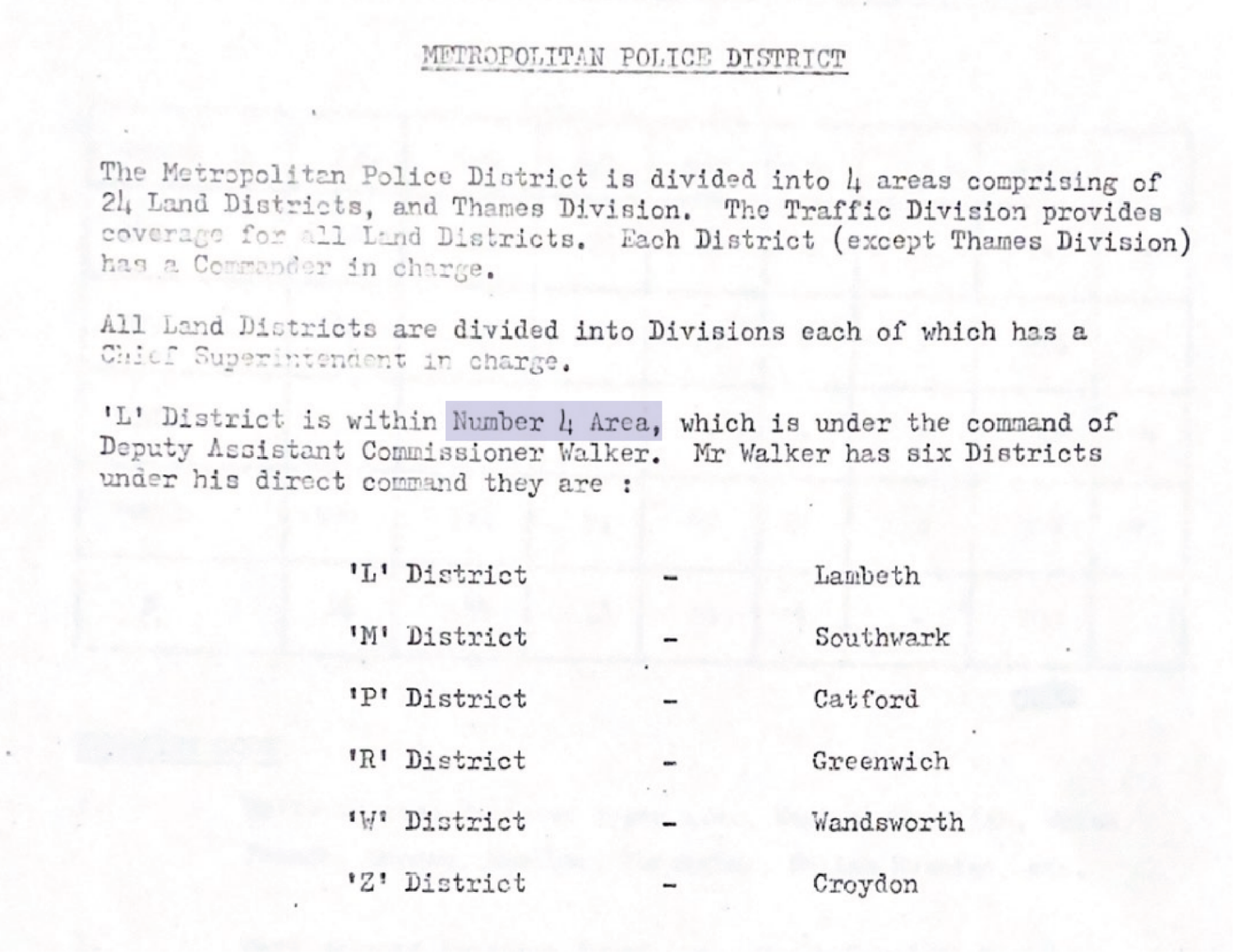

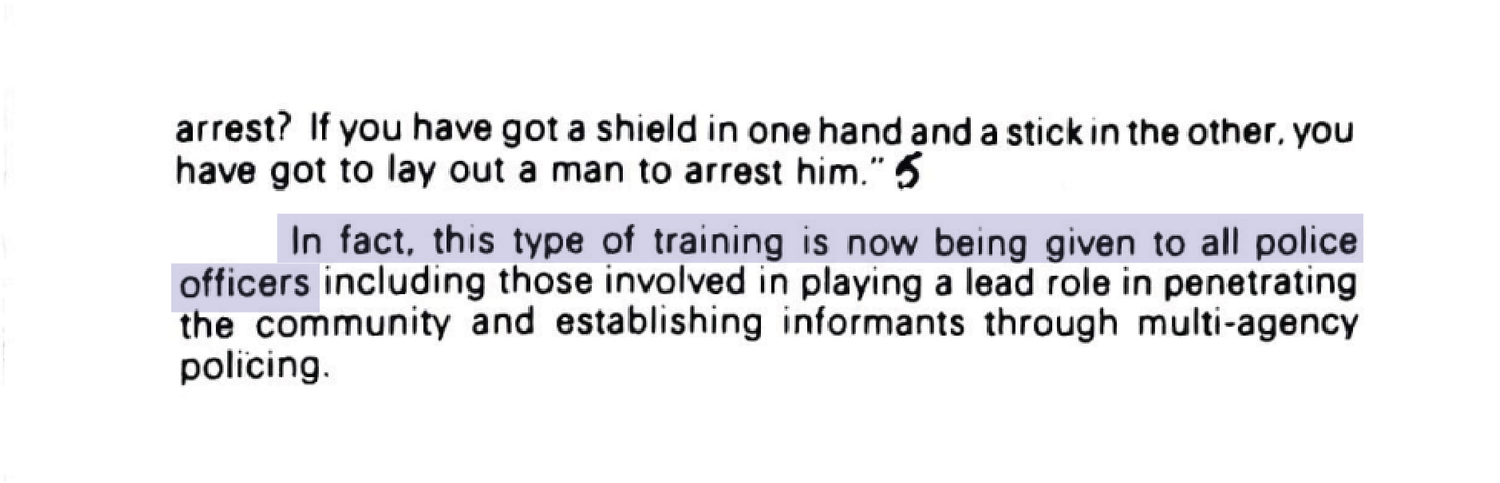

Individuals such as Commissioner Kenneth Newman were critical in establishing the use of violent, colonial methods of policing in mainland Britain.

Prior to 1948, Newman served as a colonial detective in the Palestine Special Branch.23 Afterwards, he was the Chief Constable of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in Northern Ireland where he was pivotal in ceding army authority to the RUC.24

Later, Newman would deploy paramilitary policing for the first time in mainland Britain during the 1985 Broadwater Farm uprisings.25

The style of policing present in London at this time was the direct product of police and military violence in the colonies and Northern Ireland.

According to Adam Elliott-Cooper, in the early 1900s, "Militarized policing [and] mass imprisonment of suspect communities" among other means of violent control were isolated to British colonies.26 In the colonies, the army and the police were often one and the same, as in Kenya and British Malaya.27

The use of militarized policing shifted during the Troubles in Northern Ireland (1960s-1990s). Techniques used in the colonies were imported to the UK to repress Irish Catholics. The use of riot police clad in armour were deployed in places such as Derry.28

Government officials used stereotypes about Black violence to justify the use of racist militarised policing techniques in mainland Britain.29 For instance, riot shields specifically were first used on the British mainland (outside of Northern Ireland) at the Battle of Lewisham in 1977.30

23 Elliot-Cooper, Adam. Black Resistance to British Policing. Racism, Resistance and Social Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

24 Elliot-Cooper, Adam. Black Resistance to British Policing. Racism, Resistance and Social Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

25 Elliot-Cooper, Adam. Black Resistance to British Policing. Racism, Resistance and Social Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

26 Elliot-Cooper, Adam. Black Resistance to British Policing. Racism, Resistance and Social Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

27 Elliot-Cooper, Adam. Black Resistance to British Policing. Racism, Resistance and Social Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

28 Elliot-Cooper, Adam. Black Resistance to British Policing. Racism, Resistance and Social Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

29 Elliot-Cooper, Adam. Black Resistance to British Policing. Racism, Resistance and Social Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

30 Greg Whitmore, “Flares and Fury: the Battle of Lewisham 1977 - in pictures,” August 12, 2017,

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/gallery/2017/aug/12/flares-and-fury-the-battle-of-lewisham-1977.

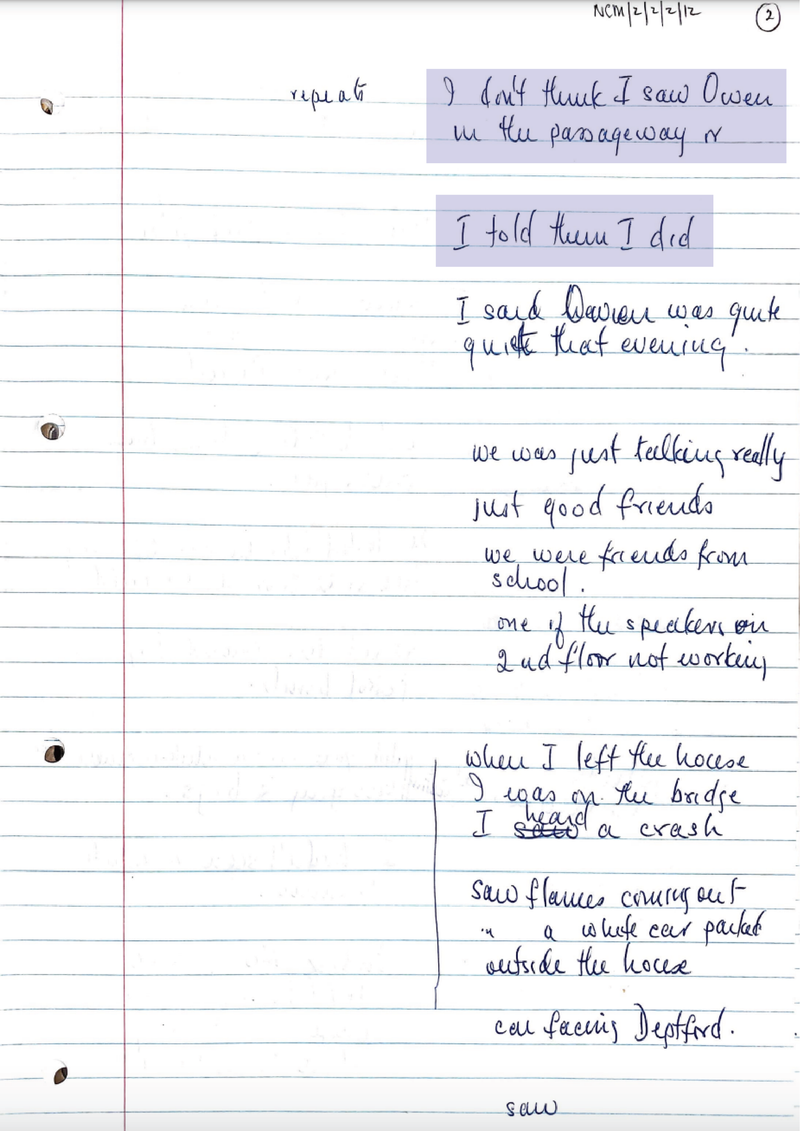

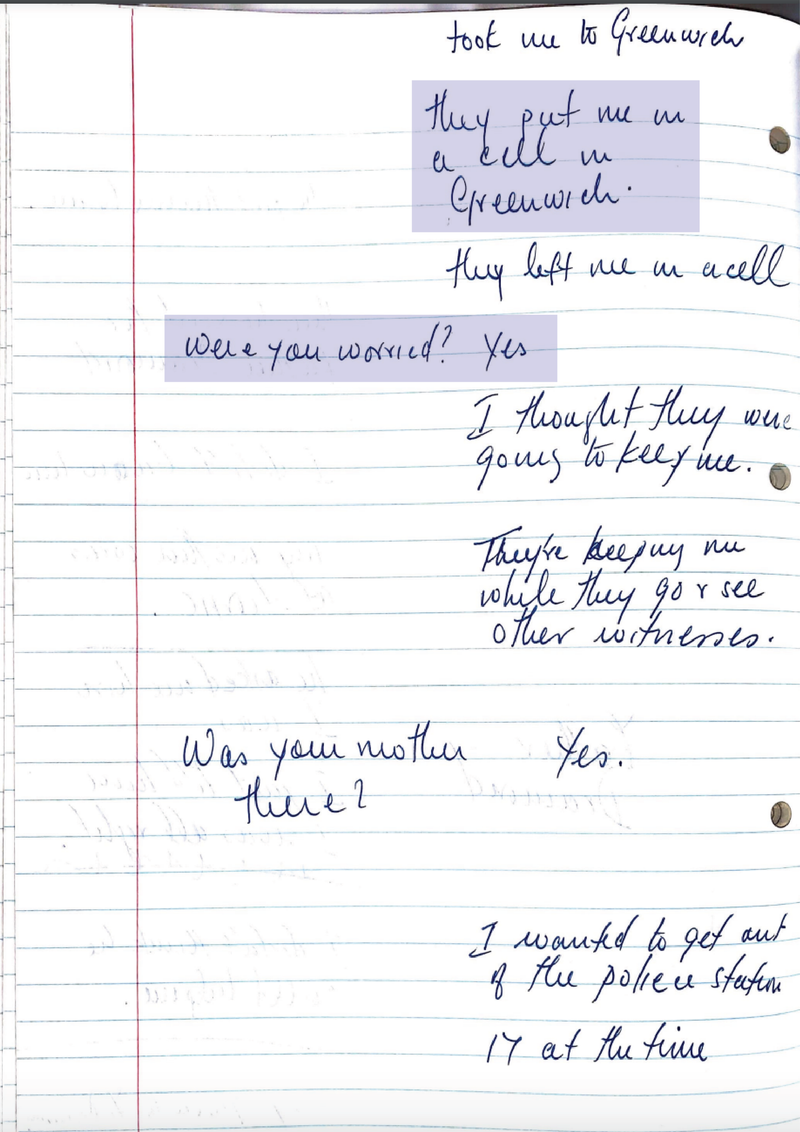

GPI, NCM 1/2/3/2, 3

GPI, NCM 1/2/3/2, 4

The Special Patrol Group (SPG) was a "crime-fighting" unit in the Met founded in 1965. In the early 1970s, the SPG's nature shifted, becoming increasingly militaristic, much like colonial counterinsurgency forces. This force targeted Black communities in London with tactics such as stop and search, snatch squads, cordons and roadblocks, raids on clubs and businesses, and other “counter-riot” strategies. This paramilitary force was in practice "an army of occupation."31 Many of these methods were drawn from the colonial context, including Palestine, Kenya, Cyprus, British Malaya, Aden (South Yemen), and Hong Kong.32

In 1980, the SPG units were formed in approximately 30 police forces.33 While the SPG was disbanded in 1986, the tactics it deployed against Black and other minority communities were "reconstituted under a different name" in bodies such as the Territorial Support Group.34

These tactics were disproportionately mobilized to target and harass Black Britons and repress movements and campaigns for social justice.

Organizers of the Black People's Day of Action were concerned about the potential presence of the SPG and the violence they would bring. Outmaneuvering the police was critical for the protesters. Therefore, despite the police informing the NCMAC that the march should begin at 11:30 AM, Howe began marching at 11 AM to disrupt police plans along the agreed-upon route.35 Linton Kwesi Johnson declared Howe the "General" for such shrewd tactics.36

31 Julian Go. "FROM CRIME FIGHTING TO COUNTERINSURGENCY: The Transformation of London's Special Patrol Group in the 1970s.

"Small Wars & Insurgencies 33, no. 4-5 (2022): 655.

32 Julian Go. "FROM CRIME FIGHTING TO COUNTERINSURGENCY: The Transformation of London's Special Patrol Group in the 1970s.

"Small Wars & Insurgencies 33, no. 4-5 (2022): 655.

33 Julian Go. "FROM CRIME FIGHTING TO COUNTERINSURGENCY: The Transformation of London's Special Patrol Group in the 1970s.

"Small Wars & Insurgencies 33, no. 4-5 (2022): 660.

34 Julian Go. "FROM CRIME FIGHTING TO COUNTERINSURGENCY: The Transformation of London's Special Patrol Group in the 1970s.

"Small Wars & Insurgencies 33, no. 4-5 (2022): 667.

35 Robin Bunce and Paul Field. “Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said” in Darcus Howe: A Political Biography, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2014), 199.

36 Robin Bunce and Paul Field. “Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said” in Darcus Howe: A Political Biography, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2014), 199.

Thatcher claimed that money had been “poured” into Lambeth towards social improvement plans. In this article from the Times on 14 April 1981, she points to £9M going towards partnership schemes and £40M to housing.

These values are comparatively low when contrasted with police spending. In FY 1980, the budget for “police services” was £2,090M (equal to £8,035M in 2022).37

A total of £320,000 was spent on the New Cross Fire investigation.38

The Times, “Violence condemned by Mrs. Thatcher.” 14 April 1981.

37 Christopher Chantrill. “Time Series Chart of UK Public Spending”

https://www.ukpublicspending.co.uk/spending_chart_1980_2021UKm_17c1li011lcn_56t51t55t

38 The Gaurdian. “Deptford: back to the beginning.” 14 May 1981.